::::::::::: ::::::::::: ::::::::::: ::: :::: ::: ::::::::::: ::: ::: :::: ::::

:+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+:+: :+: :+: :+: :+: +:+:+: :+:+:+

+:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ :+:+:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+:+ +:+

+#+ +#+ +#+ +#++:++#++: +#+ +:+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +:+ +#+ +:+ +#+

+#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+#+# +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+

#+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+#+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+#

### ########### ### ### ### ### #### ########### ######## ### ###

::::::::::: :::: ::: ::::::::::: ::: ::: :::::::::: ::: :::::::: ::::::::::: ::::::: ::::::::

:+: :+:+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+:+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+:

+:+ :+:+:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ :+:+ +:+

+#+ +#+ +:+ +#+ +#+ +#++:++#++ +#++:++# +#+ +#++:++#+ +#+ +#+ + +:+ +#++:++#++

+#+ +#+ +#+#+# +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+# +#+ +#+

#+# #+# #+#+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+#

########### ### #### ### ### ### ########## ####### ######## ### ####### ########

The 1970s saw a breif flurry of TITANIUM bicycle production: the exuberant (and stumbling) birth of what would only later settle down to become an established industry. In most cases, this burst of innovation was spearheaded by auteur framebuilders who, either by luck or sheer determination, were able to locate and utilize the industrial resources that were necessary to realize their ambitions.

Early TITANIUM frame development was hampered by a number of factors: a lack of access to suitable tubing and consumer conservatism being, perhaps, chief among these. In combination with the inevitable techincal mistakes made by any trailbazing industry, these factors meant that the TITANIUM bicycles of the 1970s were largely commercial failures. Nevertheless, they inspired, and the experience gained during these times would go on to become the bedrock of knowledge upon which bigger things would be built.

Early TITANIUM frame development was hampered by a number of factors: a lack of access to suitable tubing and consumer conservatism being, perhaps, chief among these. In combination with the inevitable techincal mistakes made by any trailbazing industry, these factors meant that the TITANIUM bicycles of the 1970s were largely commercial failures. Nevertheless, they inspired, and the experience gained during these times would go on to become the bedrock of knowledge upon which bigger things would be built.

Depending on who you ask, the German builder of FLEMA bicycles Fritz Fleck may hold the distinction of having built the first TITANUM bicycles of the 1970s.

In an interview conducted by Speedbicycles, Fritz explains that, having always been an avid bicyclist (and later pro racer), he gained the basic skills necessary for frame construction while working as a plumber. "At first, I brazed [bicycle frames] on the floor. Later on I built myself a jig when friends also asked me to build frames for them."

Claiming to have been inspired by, among others, a possible Porsche-built TITANIUM frame, Fritz sourced tubes from the Steinzeug company (of Friedrichsfeld) in order to build his own. Assembling a complete TITANIUM frame at that time would prove to be an arduous process, requiring hand-tapering and machining of all the small parts (droputs and braze-ons) from stock. His first protoype copied the tube diameter measurements of similar steel bicycles more-or-less exactly, and as a result proved too flexible to race safely. "My test cyclist Karl Mertes crashed a prototype in a race. While going downhill he pedalled so fast that the frame developed a bad shimmy and he lost control." It was this experience that would prompt Fritz to add the trademark gusset plates to his limited-production frames. Internal reinforcements in the fork crown are less visible, but still noteworthy.

The July 1974 Bike World review noted the comparatively brutal and unrefined look of the FLEMA test bicycle, and indeed the unfiled welds are rather rough. Additionally, the FLEMA frames are not particularly light, with the end result being that complete FLEMA bikes tend to weigh as much as, if not more than, the lightest steel contemporaries (as we can observe below). Finally, the ride quality of the FLEMA was reported to be essentially like that of a steel frame. Considering all of this, we may be excused for wondering if the use of TITANIUM in the FLEMA frames was, ultimately, worth the price. Of course, from our safely removed vantage point, there's no harm in enjoying their uniqueness, if nothing else.

>>> 1971/1972 "FLEMA Super"

(Images sourced from Classic Rendezvous)

Here we can clearly see the conspicuous use of drilled-out reinforcing plates or gussets in order to address flame flex issues. This Super model sports gold Mafac center-pull brakes, and the frame is virtually free of braze-ons. The 1971-1972 date is an estimate.

>>> 1972 "FLEMA Titan"

(Images sourced from Tour Hautnah)

Here we have some rare images of Günter Haritz with the West German Olympics team, showing off his FLEMA Titan in Munich, 1972. The West German team won the pursuit competition with a final time of 4:22.14. A video of one of the teams races, with the FLEMA Titan visible in action, can be viewed at the Tour Hautnah page linked above. The Titan model appears to be similar to other FLEMA bicycles of the period, with the obvious difference being that it possesses track-style dropouts and has no provisions for brakes. The reinforcing gussets are difficult to see in these pictures, but they are there.

>>> 1972 "FLEMA Campionissimo"

(Images sourced from Speedbicycles)

Externally, the main difference between this Campionissimo and the Super above it is (what appears to be) an aborted attempt at adding internal cable routing through the top tube. This bicycle is a 56 cm (c-c) and weighs 9.4 kg, or 20.7 lbs as pictured.

>>> 1975 "FLEMA Titan"

(Images sourced from Speedbicycles)

Here we have a relatively late FLEMA Titan (not to be confused with the Olympics winning track bike). In many ways this appears to be the most refined of the FLEMAs that I've been able to find. Braze-ons abound (except on the bottom bracket), the seatpost binder is a svelt and rounded number, and the dropouts are minimalist in comparison to earlier frames. The reinforcing gussets are also smaller, although this may simply be proportional to the smaller frame size, rather than being linked to any chronological evolution. The bicycle is a 49 cm (c-c) and weighs 8.4 kg, or 18.5 lbs as pictured.

While the three green mice are cycling luminary Pino Morroni's logo, most of his TITANIUM bike designs were built in close cooperation with (or actually by) Cecil Behringer.

Today, Pino Morroni is considered to be somewhat of an obscure figure in the cycling world--but those who are in the know tend to regard him has having been a visionary, if not an outright genius. There's certainly no arguing that he was an innovator, and at one time his special lightweight components graced the frames of top racers around the world (Eddy Merckx being only the most well known of these).

The Retrogrouch has a good writeup about the life and times of Pino, Classic Rendezvous details several of his impressive creations, and the Pino Morroni, Telavio Facebook Group contains a trove of rare photos. Documents from both Morroni and Behringer are archived at Velostuff. Additionally, the host of the Youtube channel "The Yellow Sheldon," John, has two recent videos discussing Pino's bottom bracket and quick release designs.

That having been said, much of what has been written about Pino can justifiably be classified as heresay. In some cases, details in different stories don't add up. What follows is my best attempt at presenting a coherent picture of Pino's forays into TITANIUM fabrication and design.

Hailing from Italy and having had extensive experience with machining, Pino designed numerous components (most of which incorporated TITANIUM or magnesium elements) including an early sealed-cartridge bottom bracket (patent US3903754A), a highly effective quick release assembly (patent US61117675A), and a family of lightweight adjustable seat posts (patent IT1040933B), which were reviewed in the August 1974 issue of Bike World Magazine. From our standpoint, however, one of Pino's most interesting components was his highly unorthodox wheelset.

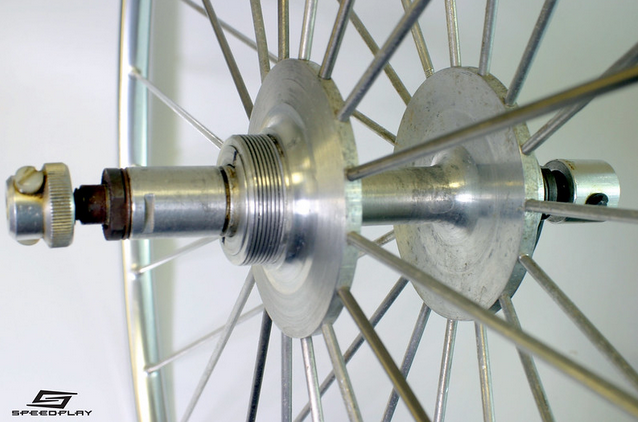

Sometimes known as "tripple nut wheels," the major components of these sets (apart from the rims) are reported to have each been hand machined by Pino from TITANIUM stock--including the spokes! The design and construction of these wheels was certainly unique in their time: the thick-gauge spokes are threaded on both ends, one end threads directly into the hub flange, while the other end hosts two nuts which "sandwich" the proprietary Ambrosio rim into place. By completely eschewing standard wheel tensioning principles, these wheelsets could be built with radial spoke patterning throughout, and were considered by Pino to have been "unbreakable" (variations can be found with single-cross lacing on the rear wheel, and different methods of securing the spokes to the flanges, including the one which gave rise to the "tripple nut" moniker).

"Shimano’s sales manager, Wayne Stetina along with his brother, Dale, used Pino’s products with great success. Wayne recalled that Pino’s wheels carried him to victory in several races. He road [sic] them in the TTT at the Montreal Games and Dale rode them at the Junior World Championships. Wayne said, 'the wheels were very fast.' Mike Fraysee confirmed that Greg LeMond won a silver medal at the 1979 Junior World Championships astride a bicycle equipped with Pino’s wheels and a bottom bracket." (Pino Morroni Obituary).

Having worked with TITANIUM to construct bicycle components, Pino was, not surprisingly, also interested in building complete TITANIUM bicycle frames. In 1971, Pino teamed up with Cecil Behringer to do just that.

Behringer was a long-distance racer with a Phd in metalurgy. It was said that "his specialty was joining the impossible" (Classic Rendezvous). Several articles note that he was frequently called upon by the likes of NASA to consult on difficult technical projects. His frame construction technique, whether working with steel or TITANIUM, was certainly unlike that of any other builder.

The lugged and brazed TITANIUM bicycle that would come to be named the Pi-Behr (for Pino and Behringer) stood apart from other TITANIUM bikes of its time in almost every respect, begining with the metal itself: advanced alloys were used, rather than CP tubing. Unfortunately, while we know that this was the case, there are major discrepancies in the various stories about which alloy was used, and in what form.

One common telling asserts that the first Pi-Behr frame components were milled by Pino himself from solid 6al/4v bar stock--dropouts, braze-ons, lugs, main tubes and all. This version of the story is supported by Pino's telling of the events himself.

The image displayed at right shows some of Pino's titanium lugs.

The image displayed at right shows some of Pino's titanium lugs.

A 2014 Titanium Today article says instead that industry pioneer Clyde Forney worked with Pino and Behringer to supply them with custom sized 3al/2.5v tubing for their lugged frames. Jim Merz (posting on BikeForums.net) had this to say on the topic: "I got to go inside Zirtech back when they were making the tubing for Behringer. The alloy used for this bicycle frame tubing was indeed 3-2.5. The stays were even tapered!"

This is also corroborated by the most complete and detailed account of the construction of the Pi-Behr bicycles: the Bike Tech, Vol. 1 (1982), article titled "The Ultimate Titanium Frame?" by Fred DeLong and Crispin Miller.

The Bike Tech article (full issue found here) focuses on the creation of the nitrited Pi-Behr frames, but also describes the basic construction process. To say that these bicycles were assembled in a unique way feels like a vast understatement.

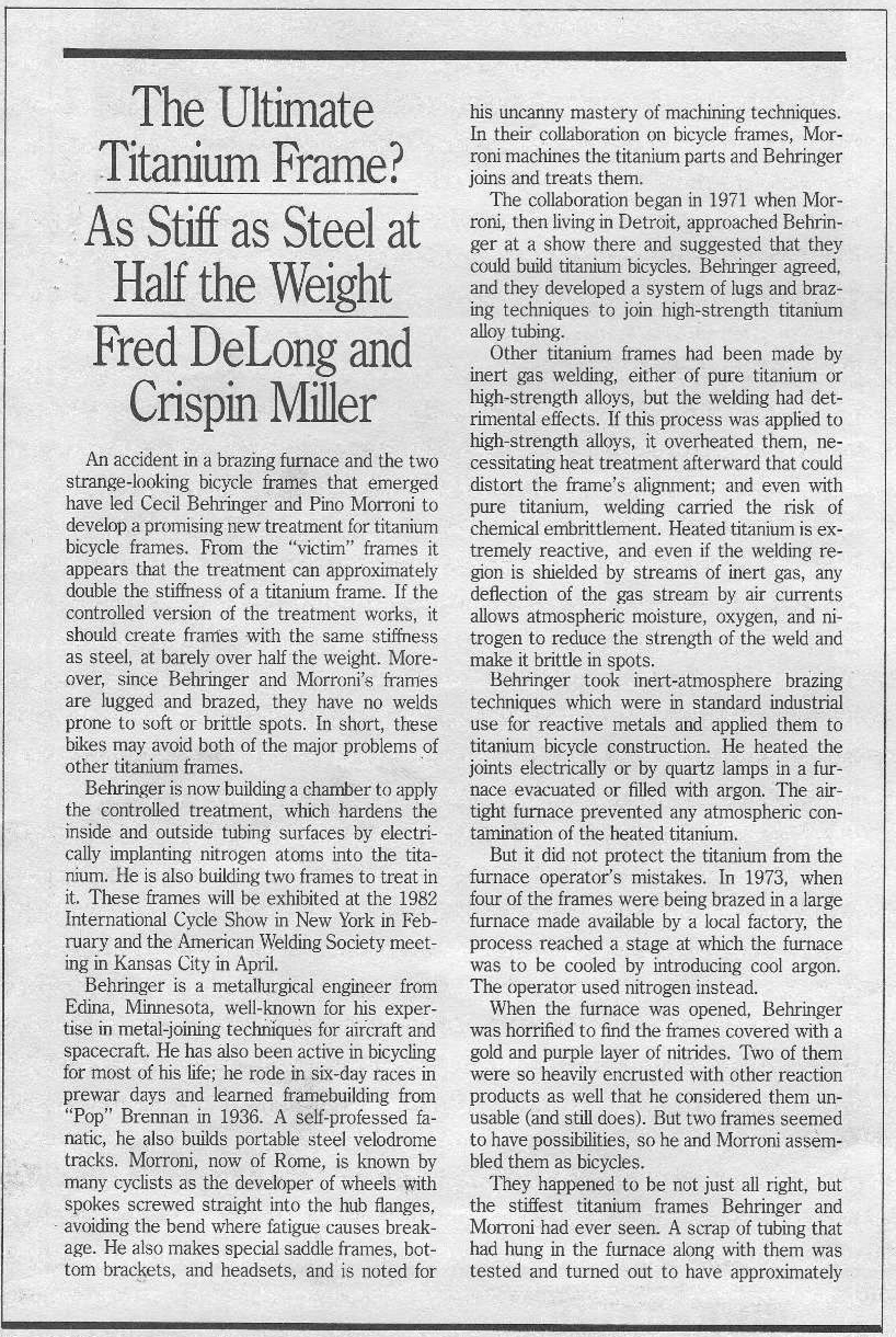

Starting with the lugs, the article states that Pi-Behr frames "are constructed from various sizes of tubing, bored and mitered (by Morroni) and then brazed with a titanium-copper-nickel filler compound by quartz lamps shining onto a small argon-filled quartz furnace. Brazing temperature is 1650°F, not hot enough to damage the alloy."

As with Behringer's custom steel frames, the braze filler compound was likely made up of powdered metals suspended in a petroleum carrier jelly (metalurgy nerds will note that 3al/2.5v TITANIUM is an α/β alloy, and that 1650°F is below the Beta Transus of 1715±25°F. The arc emited by a tig welder can fluctuate anywhere between 5,500°F and 35,000°F, for comparison).

"The assembled lug is kept at brazing temperature for 15 minutes to let the copper and nickel diffuse into the adjoining pieces of titanium. This strengthens the joint and also raises its melting point... The frame tubing is from a supply of 12 frames’ worth that Behringer had custom-drawn by Zirtech, of Albany, Oregon, when he and Morroni started making titanium frames..." This detail is confirmed by the fact that Forney had joined Zirtech in 1971. Interestingly, the article actually lists the tubing as "an alloy containing 3.5% aluminum and 2.5% vanadium"--I'll let you make up your own mind on whether that's a typo.

In any case, the tubing was "drawn to the same diameters and gauge as a set of .025-inch [0.635mm] straight-gauge Reynolds 531 (which Behringer took to Zirtech and asked them to match). The frame tubes are brazed into the lugs with a filler of nickel-copper-manganese or of aluminum-copper-tin-silicon, in an inert-atmosphere enclosure. In the current procedure, the enclosure is a 10-mil plastic bag around the frame subassemblies... For brazing, the joints are heated by electrical resistance from current applied through aluminum clamps... The brazing temperature for these joints is 1200°F and is held just long enough to wet the joint."

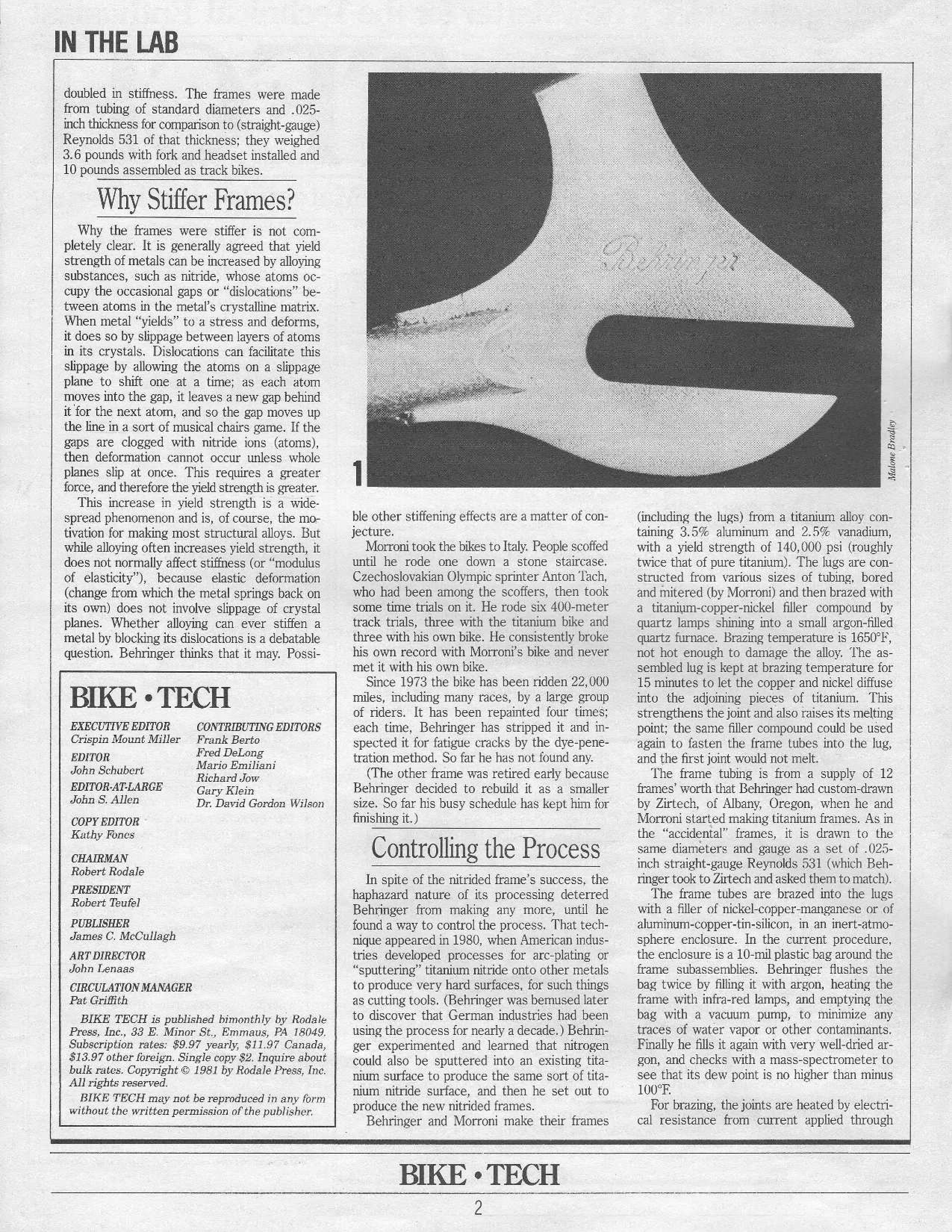

The article doesn't mention anything about controling the otherwise messy braze flow one might expect to encounter when not carefully directing the heating process with a hand-held torch, but Behringer had actually patented a slurried compound useful for confining wet brazing filler in 1970, so this may have come in handy. You can see some close up-pictures of brazed Pi-Behr dropouts (never assembled into a complete bike) here and here. As shown in the second picture, Campagnolo cast horizontal TITANIUM dropouts (#1010/A) with accomodations for adjuster screws for Pino and Behringer, which were also later used by Coassin.

All of that making sense? No? Whatever. Moving on.

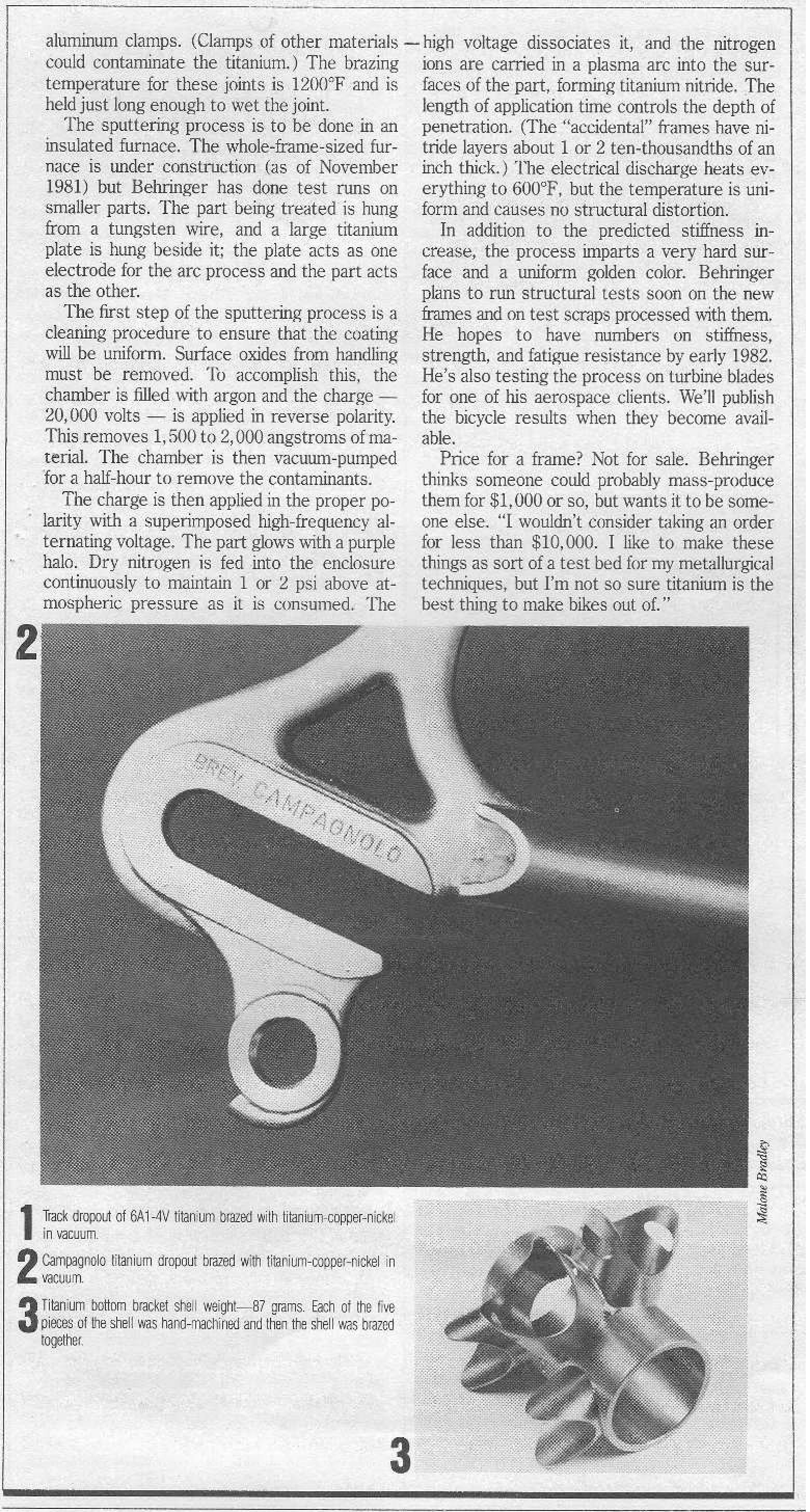

The main focus of the Bike Tech article, as stated above, is actually on the nitriding of some of the Pi-Behr bikes. The story goes like this: one day, when Pino and Behringer were having a batch titanium frames brazed in a large industrial furnace, the technician running the furnace accidently flooded the chamber with gas nitride instead of argon during the cool-down phase, and the resulting super-frames were as "stiff as steel."

When I first read the story of the accidental frame nitriding in the July 1982 issue of Popular Mechanics (posted below), I took it to be apocryphal. It sounds too much like Peter Parker getting bitten by a radioactive spider and turning into a super hero. Pino and Behringer were salesmen, after all, and may have embellished some (or all) parts of the story. DeLong and Miller, however, support this telling, and back it up with just enough facts to make it seem legitimate. To their credit, they acknowledge that nobody knows exactly why the overall stifness of the frames was increased (roughly doubled) by nitriding them in that manner. For those who don't know, nitriding typically changes the tribological properties of metals, lowering the coefficient of sliding friction and increasing abrasion resistance, surface hardnes, and yield strength, but typically does not impart measurable whole-component stiffening. As the authors note, "while alloying [with nitrides] often increases yield strength, it does not normally affect stiffness (or “modulus of elasticity”), because elastic deformation (change from which the metal springs back on its own) does not involve slippage of crystal planes. Whether alloying can ever stiffen a metal by blocking its dislocations is a debatable question. Behringer thinks that it may. Possible other stiffening effects are a matter of conjecture."

So... yeah. Who knows what's going on there. Behringer was supposed to have had some test samples analyzed, but if this was ever accomplished, the results have been lost.

Out of the several frames that got nitrided, only one was finished and assembled into a working bike. Olympic sprinter Anton Tkáč "rode six 400-meter track trials, three with the titanium bike and three with his own bike. He consistently broke his own record with Morroni’s bike and never met it with his own bike." Sounds pretty good. "Since 1973 the bike has been ridden 22,000 miles, including many races, by a large group of riders. It has been repainted four times; each time, Behringer has stripped it and inspected it for fatigue cracks by the dye-penetration method. So far he has not found any."

So, apparently, the accidentaly nitrided frames were not only twice as stiff as a regular TITANIUM frame constructed with tubes of similar dimensions, but they also held up to significant abuse and were not overly brittle. No wonder Behringer was reported to have worked on building a chamber for nitriding more frames, albeit under more controlled conditions (using a "sputtering" method). No surviving reports indicate that Behringer followed through with these plans, however. I think it's possible that he tried this procedure and that it did not produce the same frame stiffening effect, given that different methods of nitriding TITANIUM produce different types of surface treatment. It's sad to think that the same result might never again be achievable, given that the initial, accidental nitriding was relatively uncontrolled, and therefore difficult to replicate. Luckily, we now have a much easier and more reliable way of doubling the stifness of TITANIUM tubes: give them a larger diameter.

(Source: Popular Mechanics, July 1982)

The above article says pretty much the same things as Bike Tech, with fewer details but more pictures.

Unfortunately, neither solid dates nor production numbers are available for the Pi-Behr, or any of Pino's TITANIUM frames. DeLong and Miller state that Pino and Behringer started working on the project in 1971. At some point, Pino (understandably) abandoned the lugged TITANIUM design, and instead had welded frames made to his specification.

For more information on Pino's later frames, jump to his article in the

>>> "Pi-Behr"

(Images sourced from Classic Rendezvous).

As if being constructed of lugged and brazed TITANIUM wasn't unique enough, the Pi-Behr track model at left also features a left-hand drivetrain and has small diameter tubes brazed into the frame at various points in order to counteract flex and vibration (a practice borrowed from aviation design, which Pino would carry over onto many of his steel frames). The red frame at right being shown off by Mr. Morroni himself appears to be another Pi-Behr, painted, for reasons unknown, with red primer. It is reported that, at one time, Pino's TITANIUM forks could be ordered retail from Richard Sachs (although in personal communications Mr. Sachs has, at least indirectly, contradicted this claim).

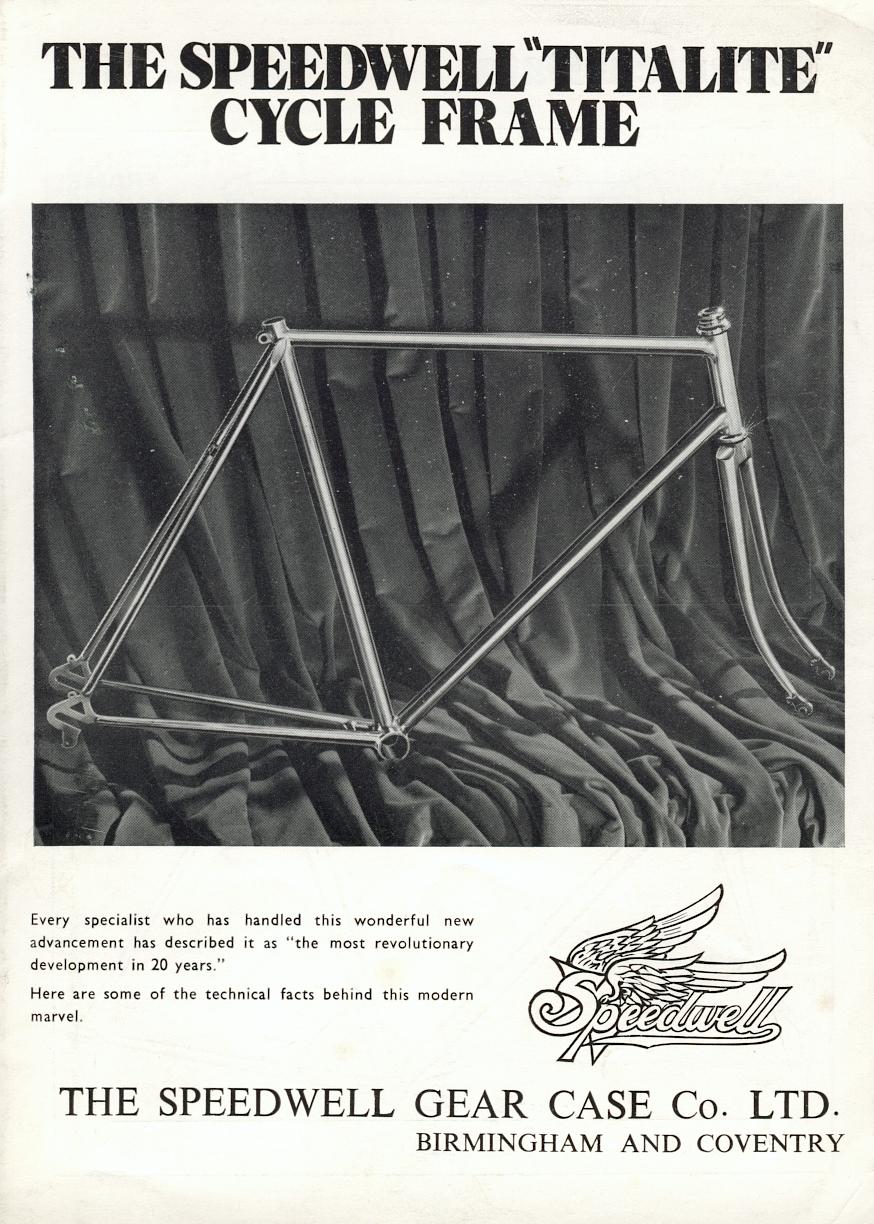

We are lucky to to have at our disposal a large sum of information regarding the Speedwell bicycles. The Classic Rendezvous page on the manufacturer has quite a few photos and other information. There is also a good write-up on the Rotorburn forum. And, of course, there is the 1974 Bike World review.

The Witton, Birmingham-based Speedwell Gear Case Company was, in the late 1960s, familiar with TITANIUM fabrication through its work on racing cars and aircraft. It was around this time that the Birmingham Small Arms Company (BSA) approached Speedwell with an ambitious project to build TITANIUM motocross frames. While the BSA endeavour would prove to be both insanely expensive and largely unsuccesful, Speedwell did gain a great deal of experience with two-wheel TITANIUM frame production in the process, and, some time around 1972, decided to produce a TITANIUM bicycle. Noted bicycle eccentric and ultra-long-distance racer Peter Duker was evidently heavily involved in the production effort.

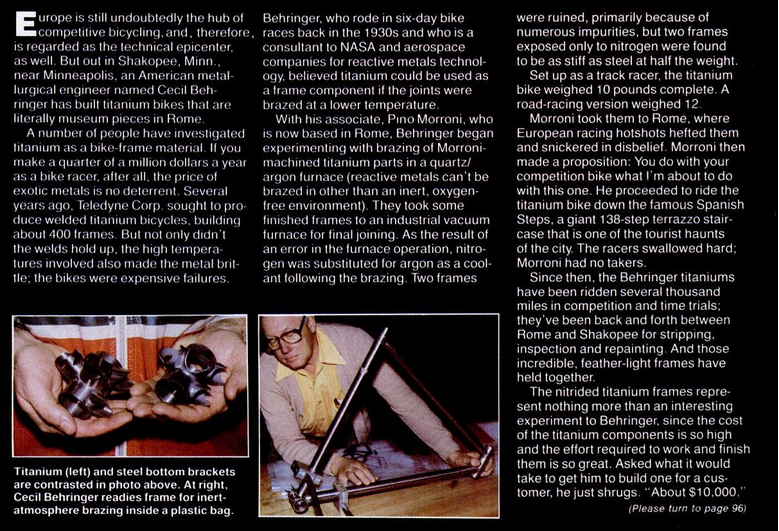

Speedwell knew that they would need help building confidence in the mysterious new metal, and their ability to craft it properly, if there was to be any hope of winning over European customers (of course, a TITANIUM FLEMA had already been raced in the 1972 Olympics, but this had evidently not done much to awaken interest in the wider market). Knowing that race results fueled sales, Speedwell set their sights on Bic team racer Luis Ocaña and, using UK distributor Ron Kitching as a go-between, a deal was struck, leading to the delivery of a Speedwell TITANIUM bicycle frame to the Dauphiné Libéré stage race in 1973 for testing. The frame would go on to be used in several mountain stages of that year's Tour De France, with the end result being Ocana's victory over Eddy Merckx (Rotorburn).

We may never know the exact reason why the Bic team decided to have Ocaña only ride his Speedwell during certain stages of the tour, but we may speculate that part of the issue was--you guessed it--excessive frame flex. While the Bike World reviewers of a Speedwell in 1974 noted the exceptionally clean and classic appearance of the frame, their judgement regarding its ride quality was harsh indeed, calling it "not suitable for any category of serious riding," as well as "spongey," "mushey," and "dead." No doubt this was the result of Speedwell's slavish adherance to classic (meaning, steel-based) frame design parameters. Others complained about the Speedwell's "rangy wheelbase, gappy clearances and relaxed angles"(Rotorburn).

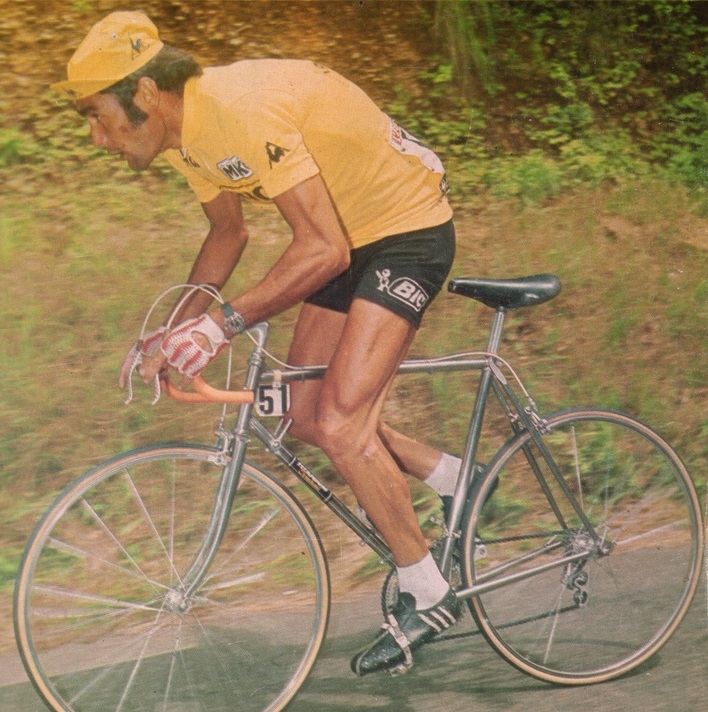

Interestingly, Roger St. Pierre, writing for International Cycle Sport in 1975, suggests that, by that time, the performance problems associated with earlier frames had been worked out. He must have been very impressed indeed, because the next year he had Speedwell build an experimental track frame to to his specifications (using even thicker tubing). Having tested the track frame, St. Pierre called it "the most responsive track bike I've yet ridden" ("The Move Toward Titanium").

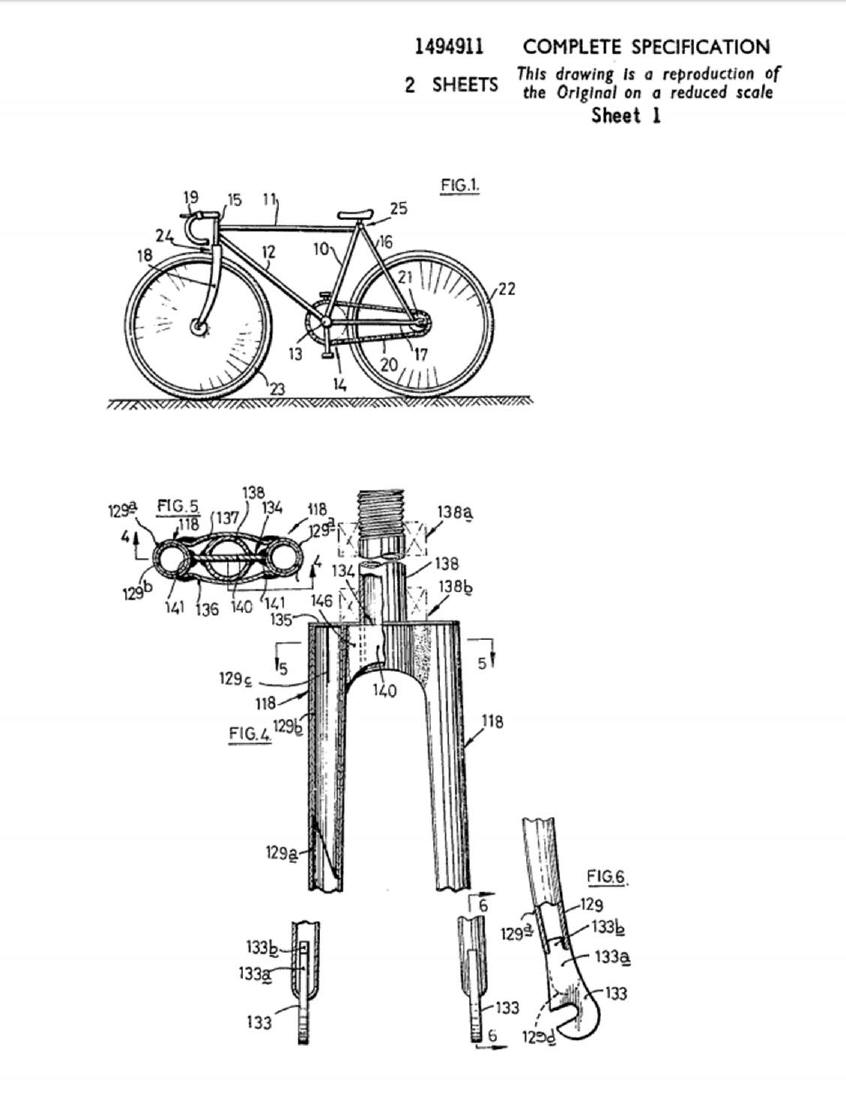

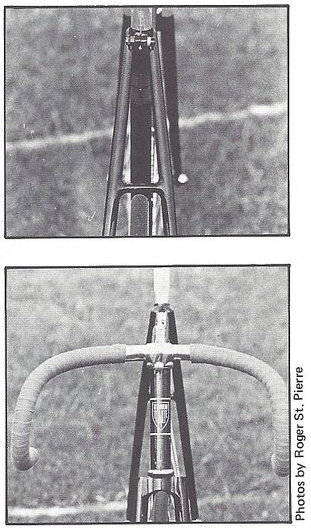

Concerning the details of the evolution of the standard production Speedwell TITANIUM bikes, little can be gleaned from their outward appearance. At least on a superficial level, if you've seen one Titalite, you've seen them all. A Speedwell representative, speaking for St. Pierre's International Cycle Sport article, explains that the extremely complicated fork design found on standard production Titalite's is an improvement over early prototype examples, which used a more standard fork crown arrangement, but I haven't been able to find any pictures obviously depicting the prototype fork. Presumably, the changes that led to later Titalites receiving more favorable reviews had to do with subtle tweaks to frame geometry and tubing thickness/diameter. Things like the number and location of braze-ons, as well as the absolutely massive welds, remained, seemingly, constant.

Speedwell allowed their TITANIUM frames to be branded by a large number of outfits over their aproximately five-year production span, as some of the pictures below show. Quite a few were also painted, which is somewhat unusual for TITANIUM. The company is reported to have closed down their frame manufacturing operations in 1977, never having achieved robust sales figures.

>>> 1973 "Titanum Speedwell"

(image sourced from Classic Rendezvous).

Luis Ocaña rides an early Speedwell "Titanium" during the 1973 Tour De France.

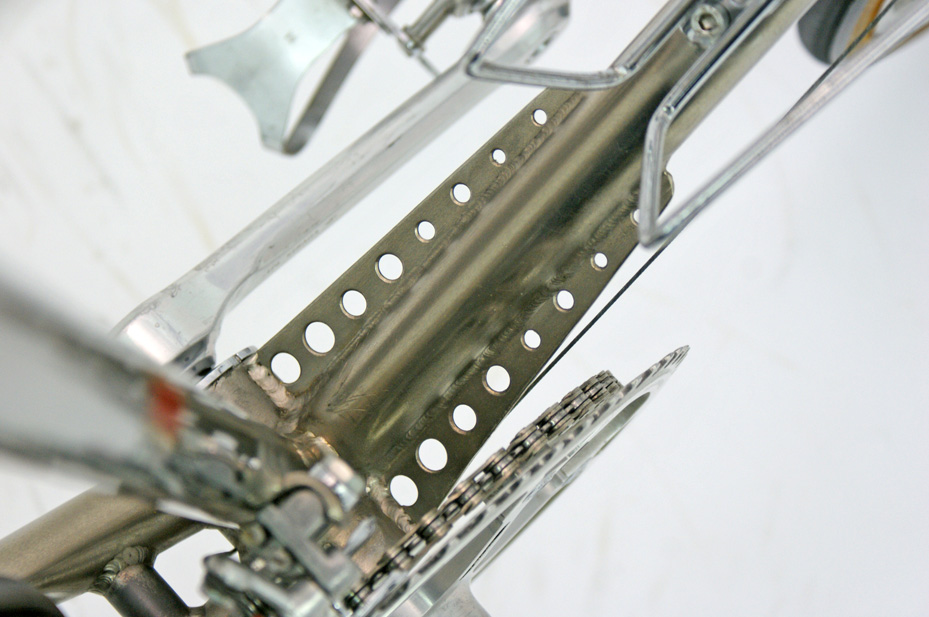

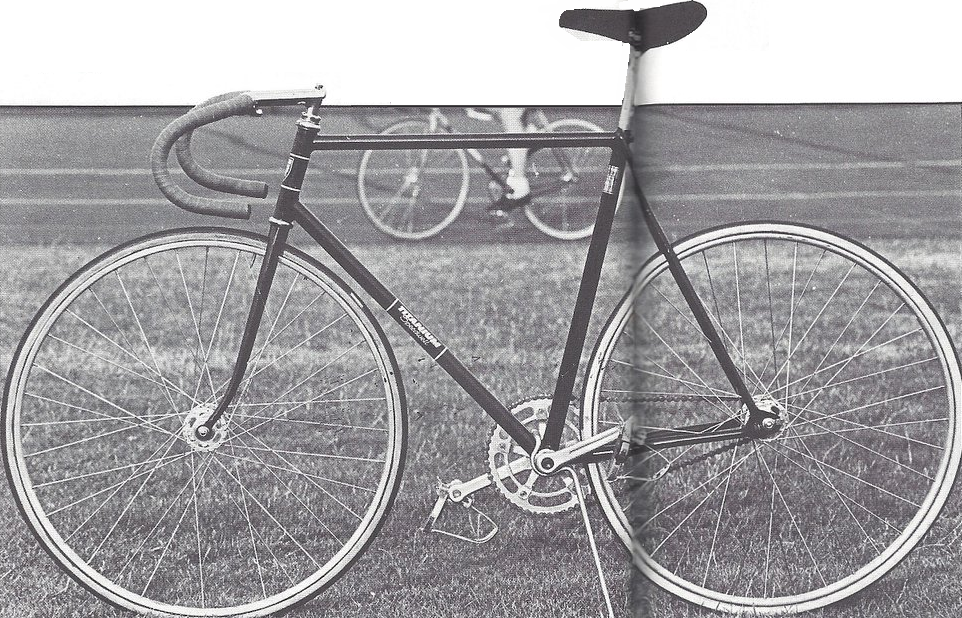

>>> 1974 "Speedwell Titalite"

(Images sourced from Speedbicycles)

This 1974 Titalite features extensively drilled components and a complete Campagnolo Record grouppo. Detail shots show the characteristic large filed welds and complicated fork. The bicycle is a 55 cm (c-c) and weighs 7.4 kg, or 16.3 lbs as pictured.

>>> 1976 "Titanium Speedwell" Track

(Image sourced from Bike World Magazine "The Move Toward Titanium").

The experimental Titanium Speedwell track bike, built to Roger St. Pierre's specifications.

>>> 1976 "Crescent Executive" branded Speedwell Titalite

(Images sourced from cykelhistoriska and r/Vintage_bicycles).

Crescent Bicycles started out as an American manufacturer, but was somehow transformed into a Swedish company around the begining of the 20th century. The Crescent Executive model of 1976 utilized a Titalite frame, and came with Campagnolo Nuovo Record grouppo, swept-back handlebars, rear rack and fenders as standard equipment.

>>> "Lamborghini Bike" branded Speedwell

(Images sourced from Speedbicycles)

This in an interesting one: multiple sources report that Lamborghini purchased and rebranded 500 Speedwell frames as commemorative bicycles some time in the early 1980s (1984 is typically referenced). This would seem to contradict the 1977 cut-off date that is often given in historical accounts of Speedwell titanium production, unless Lamborghini simply purchased old, unsold stock. In any case, some of the bikes seem to have been released with a special frame plaque detailing the commemorative release, but not all of the putative Lamborghini bikes posses them (these may of course be counterfeits). The most obvious features on these bikes, aside from the frame decals, are the custom Lamborghini branded components.

>>> Brochures & Patents

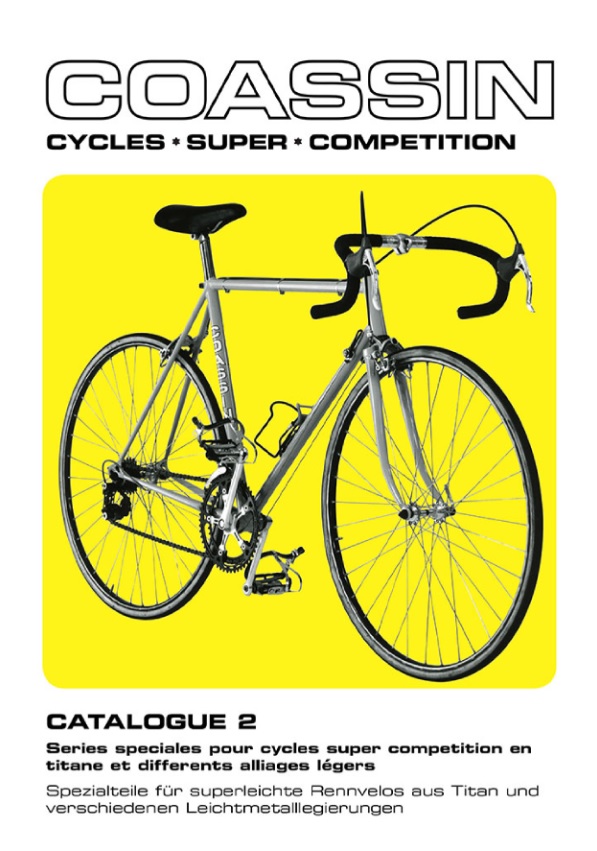

Vittorio Coassin was a framebuilder from Carouge, Switzerland. His history is not well known in the English press, but some things can be gathered. He built fine steel frames in and around the 1970s, and at some point teamed up with Alessandro Manfredi, founder of the famous Comepre S.r.l. factory in Settimo Milanese, Italy. Prior to founding Comepre, Manfredi had worked as a welder at the Aletti & Mosca workshop, adjacent to Alfa Romeo's Autodelta (we may wonder if he ever crossed paths with Amelio Riva). Manfredi was ultimately to benefit from a lucrative deal with Enzo Ferrari, which helped to establish Comepre as one of the leading fabricators of exotic metal components in Europe (source). In the early-mid 1970s, Coassin worked closely with Manfredi to have TITANIUM frames built to his standards, and at some point may have learned to weld the tubes himself (although at that time TITANIUM welding was still being done in large industrial argon chambers). According to his catalog, Coassin worked not only on titanium bicycles, but also motorcycles and race car chasis.

Coassin also designed and had TITANIUM frames manufactured for the Swiss brand/team Tigra, owned at that time by Maschinenfabrik Gränichen AG (MAFAG).

Coassin's frames were, evidently, very well made, and could be outfitted with Coassin superlight components to boot. For some reason, however, they failed to garner notice in the English press, and are not well known outside of Switzerland today.

>>> 1974 Tigra Pista Titan

(Image sourced from K-I-N-G.ch)

What a beauty! An early Coassin designed TITANIUM track racer showing the hallmark skinny tubes, understated welds and distinctive fork crown. The seat tube angle is also remarkably relaxed. The main construction is reported to be Grade 5 (6al/4v) sheet, custom formed and welded into tubes, with CP Grade 2 elements completing the frame and fork. K-I-N-G has many more detail shots of the frame.

>>> Undated Tigra "242 Titan"

(Images sourced from zugzwang.ch and veloklassiker.ch)

The Tigra 242 Titan is very similar to Coassin's own branded bicycles, with the major difference being the absence of welded top tube cable guides. The 242 Titan even shows Coassin "stamp" marks on the fork crown, leaving no doubt in the owner's mind who designed the bicycle. A fascinating bit of historical connection is revealed by the dropouts: they are Campagnolo cast titanium units, seemingly the very same ones designed initially for Pino Morroni and Cecil Behringer's brazed titanium frames! (right click on a picture and select "view image" to see it larger) Coassin's own branded frames feature identical looking dropouts but do not seem to show the campagnolo imprint. A scan of the original catalog entry for the 242 Titan can be seen here, thanks to veloklassiker.ch. To have one TITANIUM bicycle offered as a high-end model in a large and varied manufacturer's lineup was rather unusual in the 1970s, making the 242 Titan stand out from an economic perspective.

>>> 1978 Coassin "Titanio"

(Image sourced from Scampi Cicli Zurich)

The single Coassin bicycle model offered under that brand name, and very handsome. The catalog actually doesn't give a model name, but this is typically called the "Titanio" in any case. Built here with a combination of period-correct, drilled lightweight parts (and what looks like a Trecia handlebar/stem). According to the Coassin catalog, the frame is manufactured with a combination of 6al/4v and CP grade 4 tubes, making it very much ahead of its time! If I understand the catalog correctly, the frame uses tube wall thicknesses ranging from 0.8 mm up to a maximum of 2.5 mm! Perhaps the frame was not so flexible as one might expect from looking at the external tube diameters? At any rate, as previously noted, the welds are very dainty and look positively modern when compared to those of, say, Speedwell. The Coassin is also of special interest because it appears to use Campagnolo's cast TITANIUM dropouts, manufactured originally for Pino Morroni and Cecil Behringer!

>>> Guerciotti "Titanio" by Coassin?

(First image sourced from our friends at Premium Cycling, second image sourced from Giorgio's Flickr, which has lots of close of detail shots, and third image by tontovelo forum user Ian)

At some point in the late 1970s or early 1980s, it is possible that Guerciotti contracted Coassin to design and Comepre to build the "Titanio" model. The example displayed at Premium Cycling is evidently finished to a somewhat higher degree than that shown by Flickr user Giorgio, and was weighed at an impressive 17 pounds. Aside from the surface finish and "Titanio" being stamped on the fork crown of one and not the other, the first two shown examples appear to be identical. The third Titanio shown diverges from the others in significant respects, with different dropouts and internal cable routing. It should be noted that Premium Cycling reports that this model was made by Amelio Riva, of Trecia. I disagree, and instead side with tontovelo user Luc_D, who argues that Guerciotti's Titanio was welded by Alessandro Manfredi (and was therefore likely designed by Coassin). Just look at the welds, the fork, and, on the third example, the dropouts.

>>> Catalogs

(Sourced from k-i-n-g.ch)

1978 Coassin catalog, featuring the single, unnamed TITANIUM bicycle frame offered, plus lightweight components. SWITZERLAND!!!

Jim Merz, not exactly a household name, nevertheless shows up on short lists of serious contenders for the title of "best living bicycle frame builder." True, he did not build any TITANIUM bicycle frames himself (and even shunned the choice to do so). He has made a lot of TITANIUM parts though, some of them quite innovative, and it turns out he has been close to some TI projects going all the way back to the 1970s. So when I had the opportunity to interview him, I took it. Here's the interview:

Ann: What was the first titanium bicycle you encountered? What did you think of it?

JM: I actually was involved with the Teledyne Titan project early on. I met Barry Harvey when he was racing at Alpenrose for a National or other big race. He crashed and broke his leg or some other major bone. We talked about the proposed Titan frame with me, and used the Portland company Precision CastParts to make the dropouts and fork crown. I had a buddy who worked there and got to go in there. Anyway, Barry mentioned that he was going to use CP for the frame material. At that time I already decided that 3V/2.5AL was a much better choice. He rejected that idea, saying it's too expensive and CP was good enough. He was wrong, these frames fail during use. I also saw an English Speedwell frame, another CP ti bike frame introduced slightly before the Teledyne. The level of craftsmanship was terrible, ugly and not straight at all.

Ann: When did you first work with titanium yourself?

JM: Before the Teledyne Titan came out. 1975?

Ann: Can you speak a bit about the design process that led up to the creation of the S-works Epic Ultimate? Did you follow the discussion about advanced materials published in Bike Tech, for example?

JM: I had designed the normal Epic, it used 4130 CrMo lugs to connect the carbon tubes. Ned Overend wanted a super light bike for the 1990 World Championship Cross Country race in Durango. So, I got Dupont to give me some carbon fibers that were used to make satellite parts. My carbon tube maker had a prepreg machine, and used this high modulus fiber to make prepreg and then tubes for a one off bike. I had Peter Johnson make the tubes suitable for the lugs and also welded them. I built the frame in Morgan Hill. This frame was under 1 Kilogram and Ned won the title on it. There was a large clamoring for replica bikes, so I designed a production version. This frame used normal Epic tubes, with ti tubes machined by Peter and Rob Vandermark of Merlin welded them. They were assembled in Morgan Hill.

I have been interested in advanced material since before I was building bicycles. I don't know anything about the story you mention.

Ann: Some of your machining work reminds me of earlier machinists like Amelio Riva or Pino Morroni. Who, if anyone, inspired you to start modifying components?

JM: I knew Pino, he used to visit Portland. Albany Oregon was the advanced metal alloy capital of the free world during those days. I got to interface with those companies, as did Pino. I was making bike parts on a small scale from the early 1970's. I was self motivated, not influenced by other bike builders.

Ann: Your Cinelli Bivalent type hubs made use of titanium components, what inspired you to take on that project?

JM: I wanted a pair of them! It was a really time consuming project with no hope of selling for what it took to make them.

Ann: What other work with titanium are you currently engaging in, or planning on in the future?

JM: I'm not going to make parts for sale anymore, unless I find a Patron! I still have a small pile of things I have made, but I would rather ride my bike than sell trick parts that I get very little money for.

Jim Merz

Later, in a post on BikeForums.net, Jim had this to say:

"My digging around regarding titanium led me to Albany Oregon, as Mark mentions earlier this is where Teledyne Wah Chang processed titanium. The reason is that the Bureau of Mines laboratory in Albany, Oregon was the "Free Worlds exotic metal capital". This lab was where zirconium processing was developed during WWII, this material was essential for cladding uranium fuel rods in reactors. Zirconium and titanium processing is very similar, so this lab also did early work on titanium. I got to meet the director of this lab, he took me on a personal tour of the whole campus. This was a vast spread, so people used bicycles to get from one building to another. The director mentioned that they used English 3 speed bike during the 1950's and someone there decided to make a titanium frame for one! I asked if he had any photos, he could not find anything, They did make one, and it could have been before the [1956] Phillips shown in the OP!"

Very interesting stuff! Rumors have been circulating about an old TITANIUM bicycle built by engineers at Teledyne Wah Chang for some time now. Maybe some day, someone will get to the bottom of it.

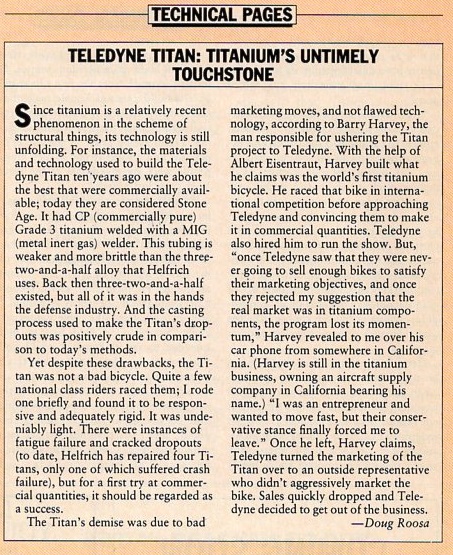

In the United States, at least, the Teledyne Titan is probably the best known and most well documented of the early TITANIUM bicycles. Articles, reviews and analyses can almost be said to abound, comparatively speaking at least. As such, I won't repeat details needlessly. It should be noted that the July 1974 Bike World review was most favorable when it came to Teledyne's offering, indicating that the Titan is worth investigating for its mechanical merits as well as its historical significance.

For more information, I recommend checking out the Classic Rendezvous Teledyne Titan page.

Pez Cycling News has an illuminating article on Barry Harvey, the man behind the Teledyne Titan, which contains a number of rare photos. Likewise, a very detailed review from the March 1974 issue of Bicycling! can also be found here. This post by joluja on BikeForums also contains interesting images of original Teledyne paperwork included with the purchase of a Titan.

My humble contribution to online research is the July 1974 Precision Metal article on the Teledyne Titan, which details the extrusion and investment casting processes used to make the frame's components.

Fun Fact: Before beginning his work with Teledyne Linair, Barry Harvey had famed early American custom framebuilder Albert Eisentraut build what was probably the first TITANIUM bicycle made in the United States, a superlight track bike. Presumably, Eisentraut was only responsible for the design, and likely delegated the actual welding to someone with experience welding hydraulic TITANIUM tubing.

(Images sourced from PezCyclingNews and Bicycle Guide Magazine Dec 1986).

In particular, the above image depicting a Teledyne booth at an unnamed trade show in the mid-late 1970s contains tantalizing details. It appears, for example, that Teledyne intended for customers to be able to order color electro-anodized frames! Also, the custom Teledyne track bike promiently featured is outfitted with an impressive complement of drillium components, including the crank arms themselves!

Miscellaneous

Random things that I wish I had more information about.

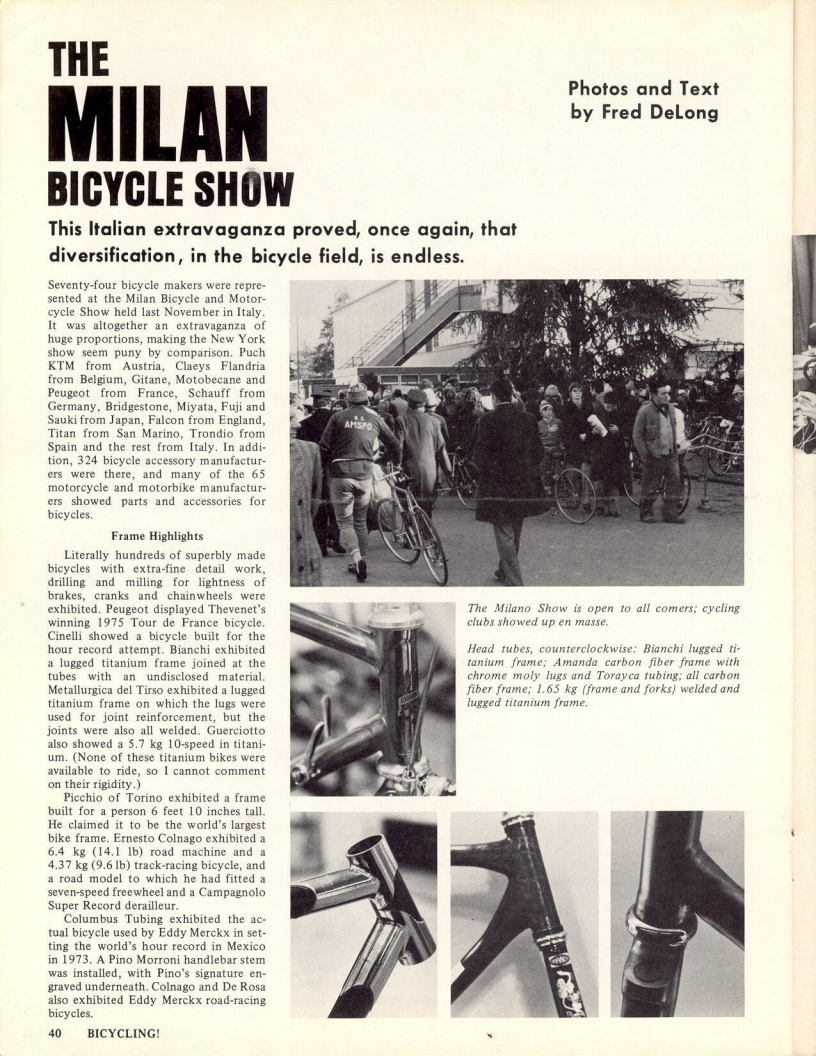

>>> 1976 Milan Bicycle Show

(Scan sourced from Velo-pages)

So apparently Bianchi made a lugged TITANIUM bicycle, bonded (or brazed?) by unknown means, in 1976??? Someone called Metallurgica del Tirso also made a welded TITANIUM frame reinforced with lugs of a sort, similar to much later designs by Mike Augspurger? And someone else made a carbon fiber bicycle frame with a very advanced, almost monocoque looking head tube? Also in attendance: a Guerciotto [sic] 12.6 lb 10 speed TITANIUM, probably made by Coassin, and Merckx's '73 hour record bike, fitted with a Pino Morroni handlebar-stem combo... surely making this one of the most interesting industry shows ever.