::::::::::: ::::::::::: ::::::::::: ::: :::: ::: ::::::::::: ::: ::: :::: ::::

:+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+:+: :+: :+: :+: :+: +:+:+: :+:+:+

+:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ :+:+:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+:+ +:+

+#+ +#+ +#+ +#++:++#++: +#+ +:+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +:+ +#+ +:+ +#+

+#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+#+# +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+

#+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+#+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+#

### ########### ### ### ### ### #### ########### ######## ### ###

::::::::::: :::: ::: ::::::::::: ::: ::: :::::::::: ::: :::::::: :::::::: ::::::: ::::::::

:+: :+:+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+:+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+: :+:

+:+ :+:+:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ +:+ :+:+ +:+

+#+ +#+ +:+ +#+ +#+ +#++:++#++ +#++:++# +#+ +#++:++#+ +#++:++# +#+ + +:+ +#++:++#++

+#+ +#+ +#+#+# +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+ +#+# +#+ +#+

#+# #+# #+#+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+# #+#

########### ### #### ### ### ### ########## ####### ######## ######## ####### ########

After the initial wave of TITANIUM bicycle design and marketing in the mid-1970s, things died down for a while. Valuable (and costly) lessons had been learned. A few of the early innovators would carry this knowledge to a new generation. Ultimately, several different lines of development would converge on the formation of a new wave of TITANIUM bicycle development: the increasing availability of 3/2.5 alloy tubing, advances in welding techniques and the drive towards innovation brought on by the emergence of the ATB/MTB phenomenon primarily. The second TITANIUM wave would be fully developed by 1988.

As in the 1970s, at first we see a mix of individual artisans (like Amelio Riva and Gary Helfrich) and established manufacturing firms (like Fuji) driving things. Unlike in the previous wave, however, in the 1980s we also see the birth of entirely new manufacturing outfits, dedicated soley to the production of TITANIUM bicycles, that will ultimately prove to be sustainable and successful. It would seem that TITANIUM's time had come, and this time it was here to stay.

|

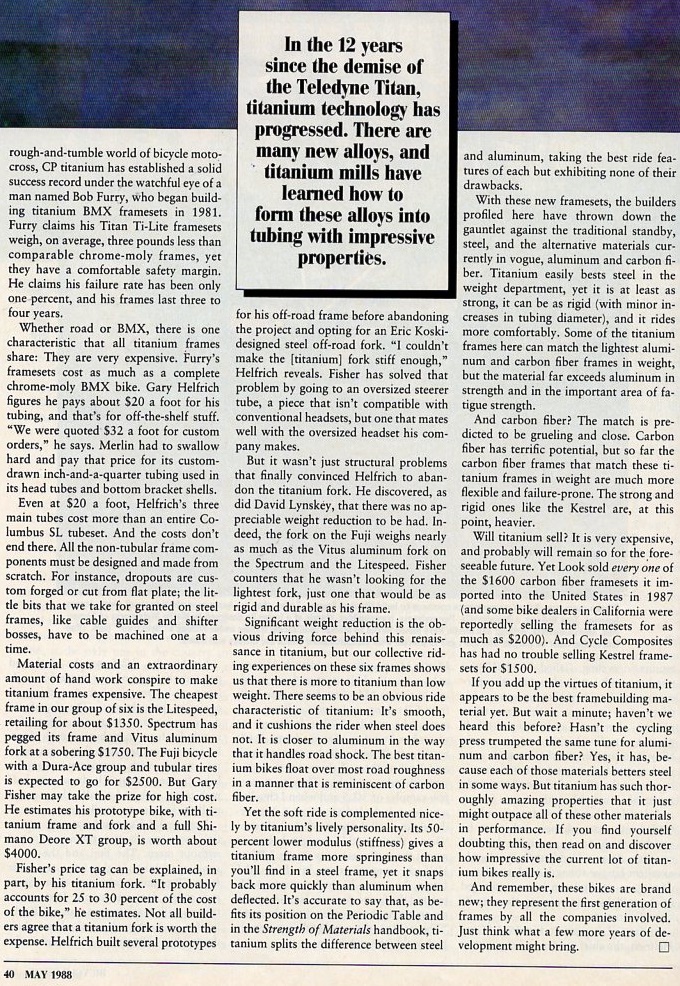

This article in the May 1988 issue of Bicycle Guide provides a general overview of the state of TITANIUM bicycle production at that time, and includes interviews with several of the key players. |

|

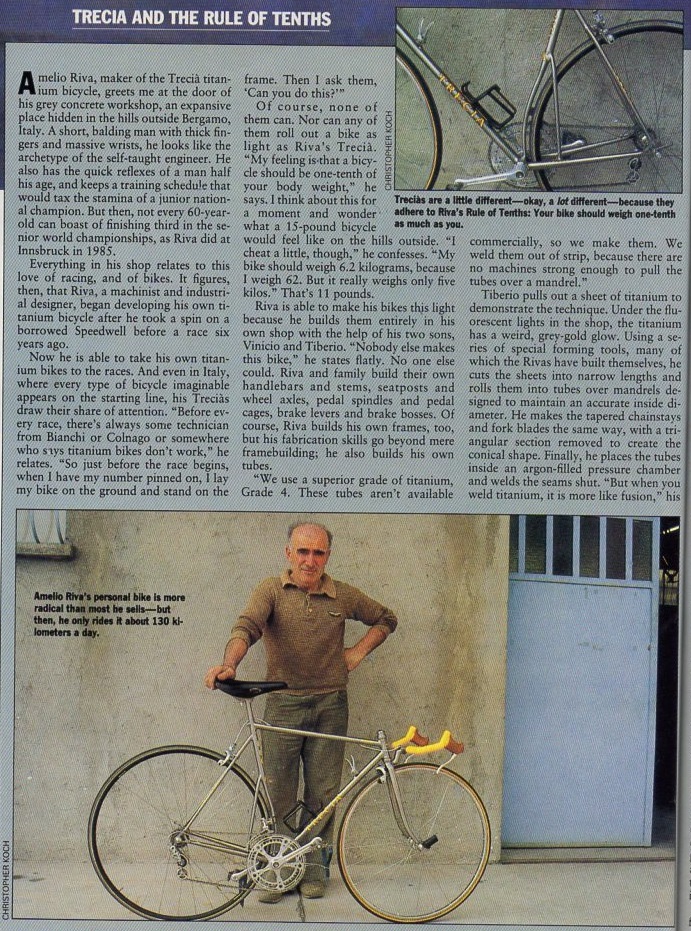

I don't know what it is about Italy and TITANIUM. Amelio Riva, like Pino Morroni, was a true pioneer among TITANIUM fabricators. But while Pino focused more on feats of unique engineering and design, Amelio, through his Trecia brand, pushed the boundaries of what was possible in terms of artistic integration and weight reduction.

Unfortunately, very little seems to have been written about Amelio in the English press. In fact, the following article is the only thing I've been able to find that goes into any detail, which is a real shame. Photos of surviving Trecia bikes confirm that Amelio and his sons elevated the craft of TITANIUM working to dizzying heights. That having been said, the comparative abundance of what are apparently Trecia frames with broken tubes on eBay might suggest that long-term durability was not among their many virtues. Well, as has been said, "it's better to have loved and lost, than never to have loved it all." Or maybe "the candle that burns twice as bright burns half as long?" Take your pick.

As is made clear in the supplied article, TITANIUM tubing was not widely available in Italy in the late 1970s and early 80s, so Amelio and his sons simply formed and welded their own shaped tubes out of TITANIUM sheet. The "simply" in that last sentence was sarcastic, in case you didn't catch that. This kind of work was par for the course for Amelio, however, since he primarily worked as an automotive machinist for Alfa Romeo. In fact, it's reported that Amelio bought his argon pressure welding chamber from from Autodelta, Alfa Romeo's (now defunct) competition department, responsible for such memorable machines as the 33TT12.

While Amelio Riva's own exploits are not well documented, his influence, both direct and indirect, is still quite visible. So, for example, the present-day bicycle manufacturer Passoni was born out of a chance encounter with Amelio and one of his Trecia's, and the early Passoni's are essentially just Trecia copies. Likewise, the Stelbel brand was created partly because of a friendly comradery between Amelio and Stelio Belletti.

The images contained in the above article depict what is surely one of the most wild bespoke TITANIUM road machines ever made. With its low-profile, integrated fork/handlebars and split seat tube, it's obvious that this bicycle was a labor of love. Reported weight fully built: 11 pounds. Incredible.

>>> Undated Trecia "Titanios"

(Images sourced from Premium Cycling, encricco's flickr and Ebay user noprit0)

Here we have examples showing Amelio's mainstay model, the Titanio. Outwardly, the Titanio resembles many of the TITANIUM bicycles of the 1970s, thanks largely to the classic proportions and the massive filed welds that almost resemble fillets. Image two depicts frame N. 196, with the dimensions marked 47x50. Included are images of the most popular custom addition found on surviving Titanos, a one-piece TITANIUM stem/handlebar, found in both rounded and more angular versions. More pictures of a Titanio can be found at Ugo Ambrosetti's Flickr.

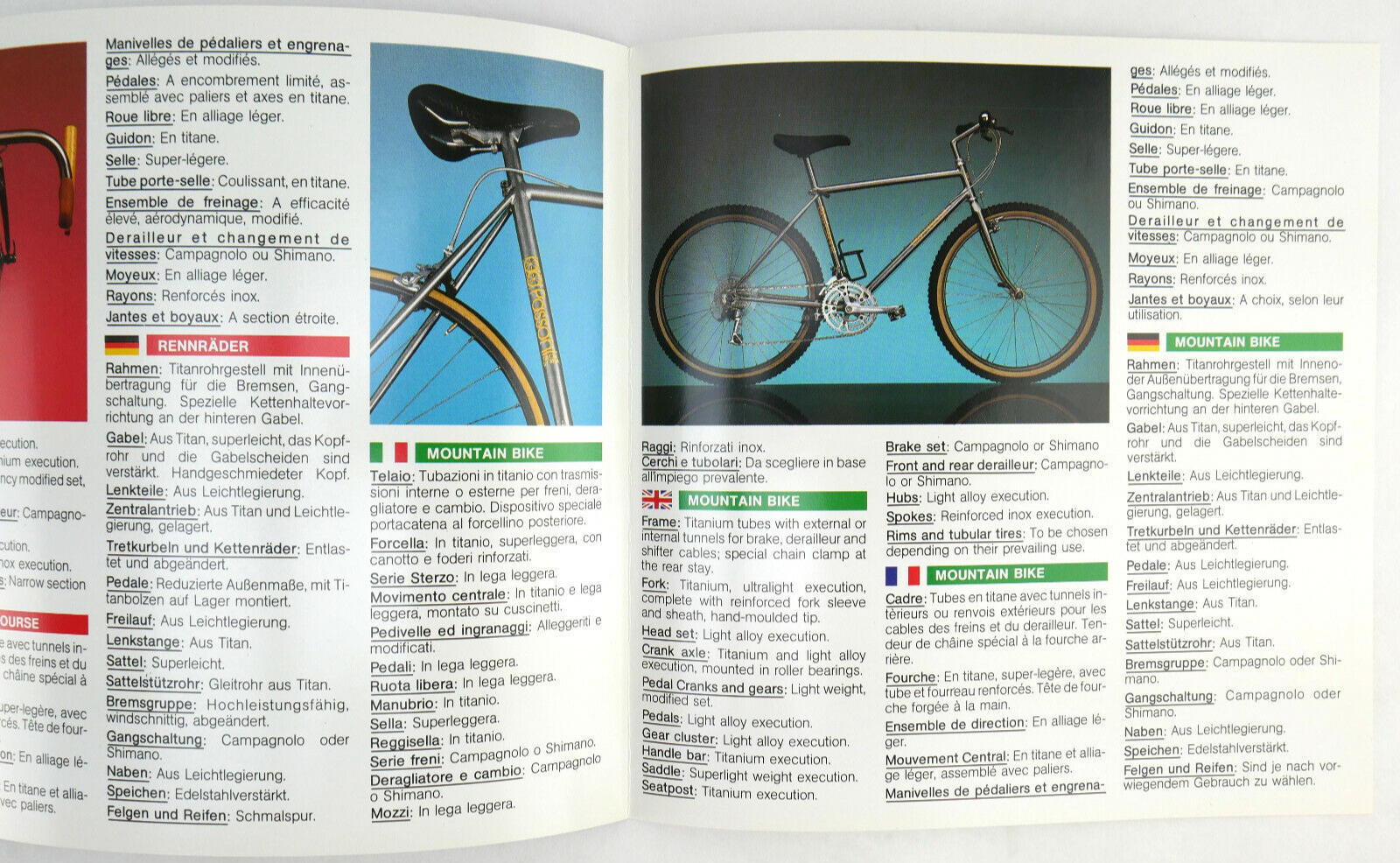

>>> Passoni "Trecia by Riva" Catalog

(Images sourced from a sadly paranoid and somewhat deranged eBay user)

This fascinating Passoni distrobution catalog, seemingly from the late 80s (or perhaps very early 90s), indicates that at one time Passoni simply distributed Trecia bicycles by Riva. The photos show beautiful examples of models with complete compliments of custom Trecia manufactured or modified components, including seat posts, saddles, stems, handlebars and brakes (If you own a physical copy of this catalog please contact me about having high-resolution scans made. Thank you!)

>>> Components purported to have been made or modified by Amelio Riva

Check out the link HERE

Developments in the BMX world are often left out of larger discussion on bicycle design. Interestingly enough, however, some of the first TITANIUM bicycle in the 1980s were BMX bikes.

According to James Foreman, his father Bert, in partnership with Ken Burleson, started building Titan TITANIUM BMX frames some time around 1982-84. The business was very much a family venture, with James coming up with the name for the project while in high school. James, along with Ken's son (reportedly named Kendal), made up part of a factory racing team.

As James reports: "The bikes were made for small kids, anyone over 11 (I can't remember the weight limits) would break them, we had a lot of problems with the neck tube breaking which is why we welded gussets to them."

It would appear that this frame weakness may have been the result of improperly-purged welding environments, as all visible welds on the unpainted frames show various degrees of blue discoloration, a tell-tale sign of oxygen contamination.

The history of the Titan brand (and its various offshoots/collaborations) is somewhat difficult to follow, but there are a number of threads on various BMX forums attempting to piece this together (see for example, threads on bmxsociety.com and bmxmuseum.com).

BMX Museum also has an official Titan page here.

Finally, Oldschoolracing.ch picks up the Titan story later, once they had become a MTB brand (assuming it was the same company).

A typical Titan Ti-Lite Mini, reportedly from 1986. As is plainly visible, the blue and yellow discoloartion of the welds indicates oxygen contamination. Reinforcing guessets and braces were necessary not only to combat frame flex, but outright breakage.

>>> 1986 Titan Ti-Lite Mini

(Images sourced from Worthpoint).

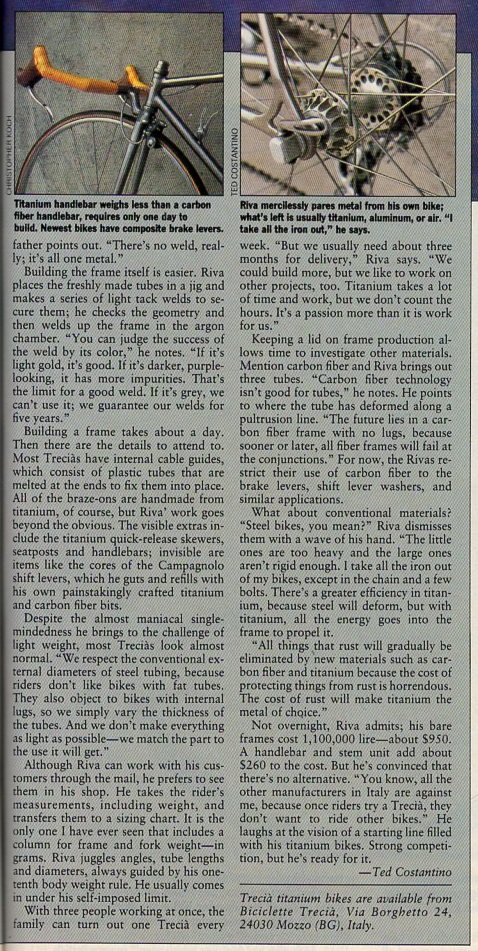

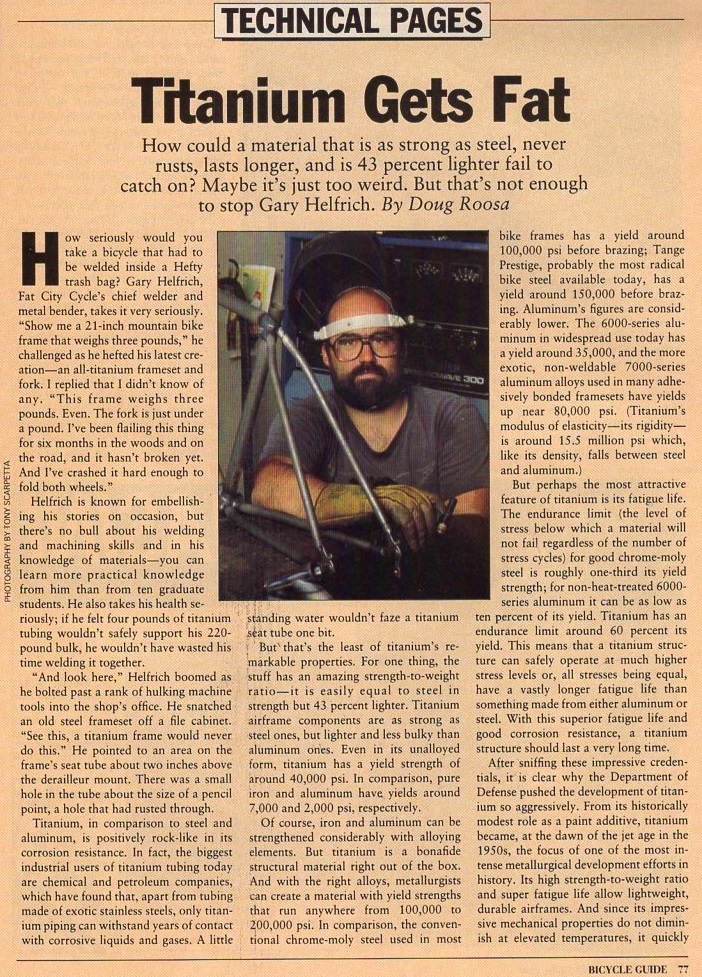

Gary Helfrich's work out of the Fat City Cycles workshop (which was sometimes, but not always, branded with the Fat City logo) is the stuff of legends. While Gary wasn't the first to build with TITANIUM, he is credited both with building the first TI off-road bicycle and dramatically improving the welding process used by bicycle framebuilders. In the 1986 Technical Pages article linked below, we find Gary welding TITANIUM frames using a plasma welder inside of an argon/helium purged plastic bag, a technique borrowed from the Airforce, and a step-up in convenience over the use of large, heavy vacuum chambers. Not satisfied with this workaround, however, Gary figured out how to use oversized cups and long post-flow when TIG welding TITANIUM, which allowed frames to be built without any sort of external enclosure (you can read more about this in my interview with Mike Augspurger).

Writing about Gary under the Fat City Cycles banner doesn't necessarily make the most sense, as Chris Chance was reportedly skeptical about the practicality of TITANIUM frames. In doing so, I am simply following convention.

For lots of pictures and information about Gary's early work at Fat City, and later Merlin, see the MerlinTitanium page on the evolution of Merlin Titanium from 1985 to 1987

As you continue to read about other TITANIUM bicycles through the 1980s and beyond, Gary's name will come up again and again, either as an individual consultant or as one of the founding members of Merlin Metalworks.

Three associates founded Rewel (Renata, Werner and Leo) bikes in Italy in 1986. At first, Rewel built stainless steel frames in a very limited capacity: "we did it in our spare time and only for friends and acquaintances" (pzzgarage). Later, in around 1988, Rewel started building TITANIUM frames that combined welded and "glued and screwed" construction. Rewel was one of the first frame building outfits to enthusiastically support MTB development in Italy, and would go on to produce some extremely advanced frames in the early 1990s.

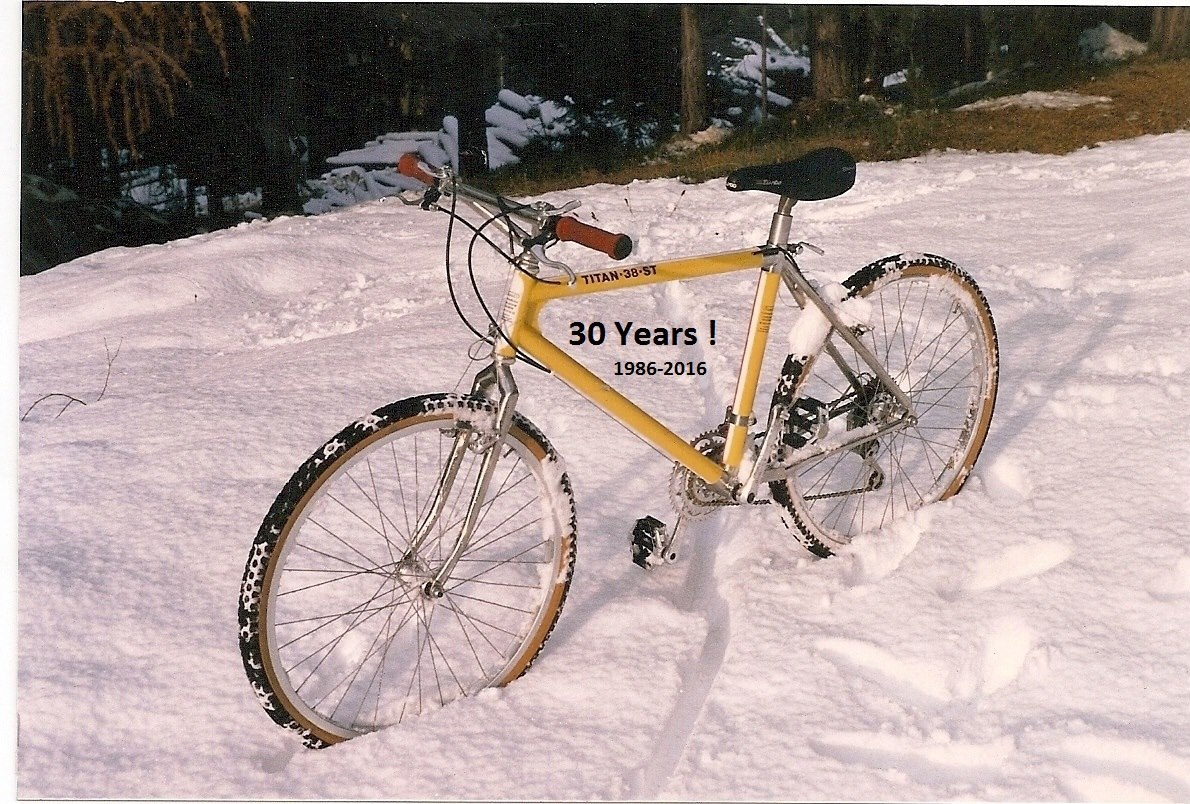

>>> ~1988 "TITAN.38.ST"

(Image sourced from Rewel Facebook page)

This Rewel shows the characteristic early frame configuration: a welded head tube cluster with reinforcing gusset, with the TITANIUM main tubes elsewhere being joined with bonded stainless steel lugs. The painted TITANIUM tubes are unique, but the Alan fork is common on very early Rewel bikes.

>>> ~1988 Rewel

Image sourced from pzzgarage)

Another early Rewel with mixed welded/bonded construction. This example has several notable features: it is fitted with early Magura hydraulic brakes, it uses only two chainrings, and it features a machine-turned surface finish. The early Rewel bikes, as with Trecia, were produced from TITANIUM sheet metal that had to be shaped into tubes. This shaping, and the ensuing welding, left a rough seam along the tubes. The machined surface finish helped to conceal the tube seam and any other visual signs of the shaping process.

>>> Undated Early Rewel

(Images sourced from Retrobike)

While the date of manufacture for this Rewel is unknown, I'm inclined to think that it comes from the late 1980s, rather than the 1990s, because of dramatic differences between it and known 1990s Rewel frames. The owner of the frame is under the impression that it is a protoype. While the joints are welded throughout and there is no head tube gusset, it was built from shaped sheet metal, rather than factory-produced tubing, and features another machine-turned surface finish.

While Pino Morroni is mostly known for his work on the lugged and brazed Pi-Behr TITANIUM bicycles of the 1970s, there are also several Pino or Telavio branded TITANIUM bicycles that appear to have been welded (not brazed) in the 1980s.

Greg Boggs, an apprentice of Pino's has suggested that a Jim Reese in Detroit might have built these later welded TITANIUM frames to Pino's specifications:

"I believe Jim Reese was a toolroom welder at Chrysler, where Pino once worked as a Master gauge builder at Dodge Main Assy.

Pino wasn't a welder. He could stick something together with a TIG welder, or tack with a MIG but that was pretty much it. The only titanium welding that I KNOW he performed, was tacking the prototype bottle cage for the triangular Pino bottle (the very bottle cage that Mark Agree has on his bike.)

There was a Syncrowave at Mike Otti's shop in Clawson, where most of Pino's work was being done but I never saw him use it.

My belief that it was Jim who was welding for him, comes from a pissed-off angry fit that Pino threw at Kinetic Systems in the late '80's. Pino was unable to get the price he wanted on a set of wheels, so he CUT THEM UP. He used my diagonal cutters to chop the titanium spokes out of the wheel which he then gathered in a bunch. He said he was giving the spokes to Jim, to use as welding rod...

I was never fortunate enough to meet Mr. Reese but you may be able to find more info from Mike Otti (he is on the pino-telavio facebook group). Mike and Pino, were business partners in a machine shop prior us meeting.

As someone who was in the scene back then, I don't know anyone in the local cycling community who would have been competent to perform this kind of work." (BikeForums).

As with so many details about Pino's work, it is unknown when, exactly, he stopped designing TITANIUM frames, or why. For those who are curious, some of Pino's products may still be on display at Kinetic Systems Bicycles in Clarkston, MI.

>>> Pino Morroni Titanium Road

(Image sourced from Facebook user Francesco Rugolo).

This bike and the one below it are, obviously, neither lugged nor brazed. The most obvious feature of this bike is the aggressive weight-forward riding bias, acheieved with relatively long chainstays, short top-tube, short front-center, and a very long (possibly adjustable) stem supported by an adjustabe strut, connected to the fork crown. It may also be fitted with another interesting variation on the tripple-nut wheels, with high, ported flanges on the rear hub and low flanges on the front.

>>> "Telavio" Titanium Road

(Images sourced from Mountain Road Cycles Facebook).

This TITANIUM frame bears the Telavio logo, which Pino adopted for his later bicycles (the name "Telavio" signaling design influenced by aviation engineering). Again we see the long, possibly adjustable stem, although it appears this time to be coupled with somewhat more standard geometry. Other features (braze-ons, fork construction, etc.) appear largely the same as the above shown example. This bicycle also sports of pair of the the true tripple-nut wheels.

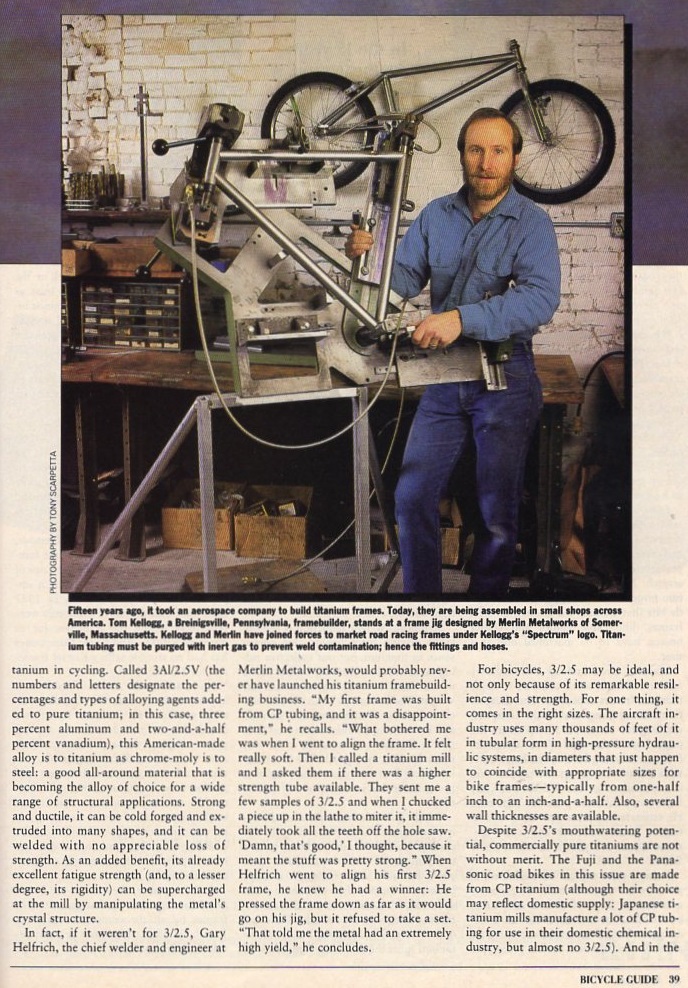

Merlin Metalworks, founded in 1986 by Gwyn Jones, Gary Helfrich, and Mike Augspurger, was one of the more important pioneers in the TITANIUM bicycle industry. Merlin's innovations were not only creative, but also often practical and lasting, setting them apart from the likes of Pino's Telavio brand or Amelio's Trecia. Merlin was instrumental in making 3al/2.5v TITANIUM the alloy of choice for framebuilders, for example. As is shown below, Merlin also produced one of the earliest modern "compact" goemetry road bikes, but they are more well know for the staggering array of prototype ATBs/MTBs that they made, most of which can be found at MerlinTitanium.com. MOMBAT has a page on Merlin's history with a number of scanned articles and reviews. An archived page, originally found at FirstFlightBikes, also contains an illuminating timeline of the company.

Older Merlin bicycles are now extremely desirable collector items, more so than almost any other brand (mostly I get yawns when I tell people that I own a rare early Litespeed--the reaction would almost certainly be more animated if it was a Merlin).

As you will see while reading other sections in this website, Merlin, due to their expertise in working with TITANIUM, was frequently contracted to build frames for other brands.

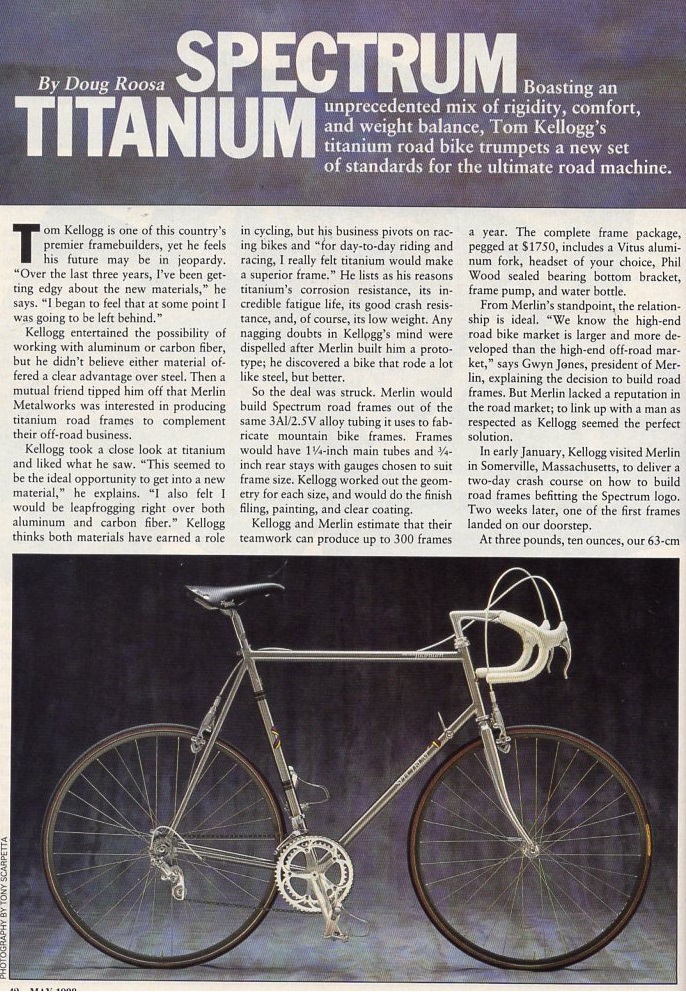

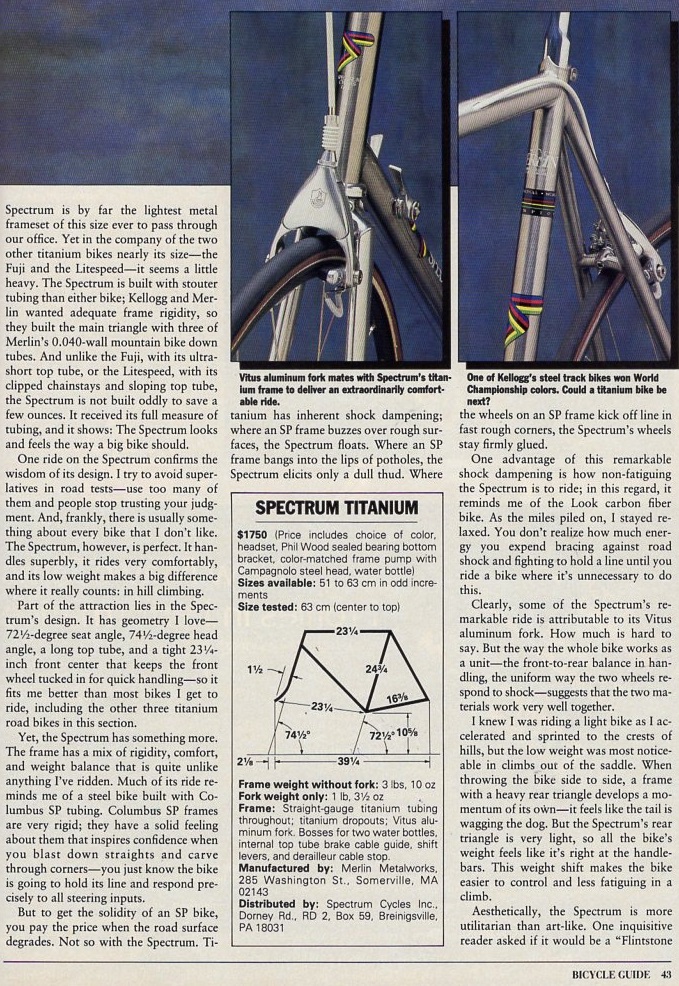

Tom Kellogg started building frames in 1976, apprenticing for Bill Boston of Sweedsboro, NJ. The fact that he would be fired from that position after only three months would seem to suggest an inauspicious start to his career. In fact, he would waste no time in making a name for himself, with Danny Clark taking the gold at two World Professional Championships in 1980 and 1981 on Kellogg frames. That achievement in particular is reflected in Tom's brand logo, and Spectrum was for a long time one of only three American manufacturers who had earned the privilege of using the blue, red, black, yellow and green rainbow of the Union Cycliste Internationale.

Tom's reputation has been that of a detail-oriented perfectionist, a builder more concerned with ride feel than marketable gimmickry (bicycling.com). Given this design influence, coupled with Merlin's technical mastery, we should perhaps not be surprised to see the Spectrum "Titanium" earning such high accolades in the 1988 Bicycle Guide review.

According to technical editor Doug Roosa, the Spectrum was "perfect."

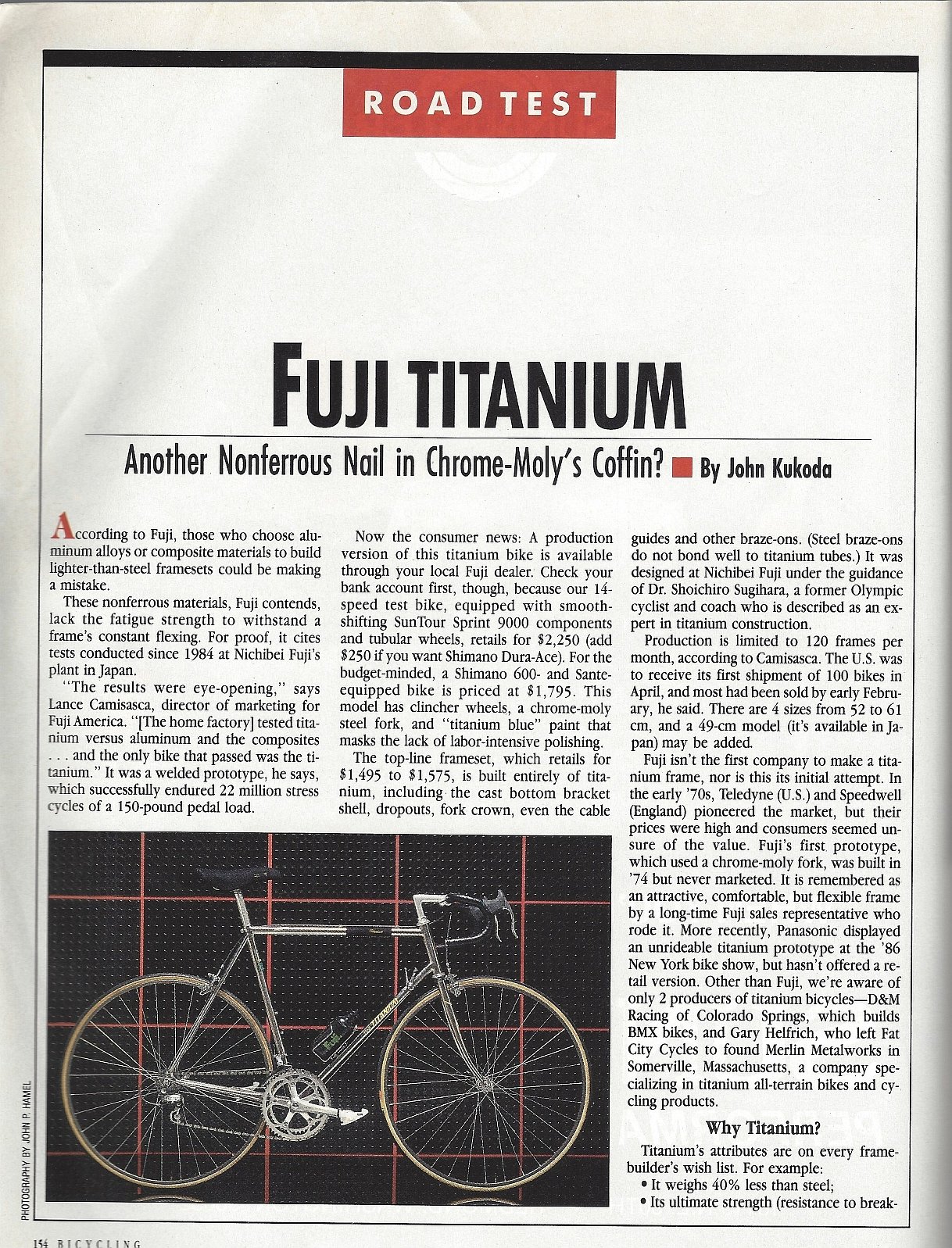

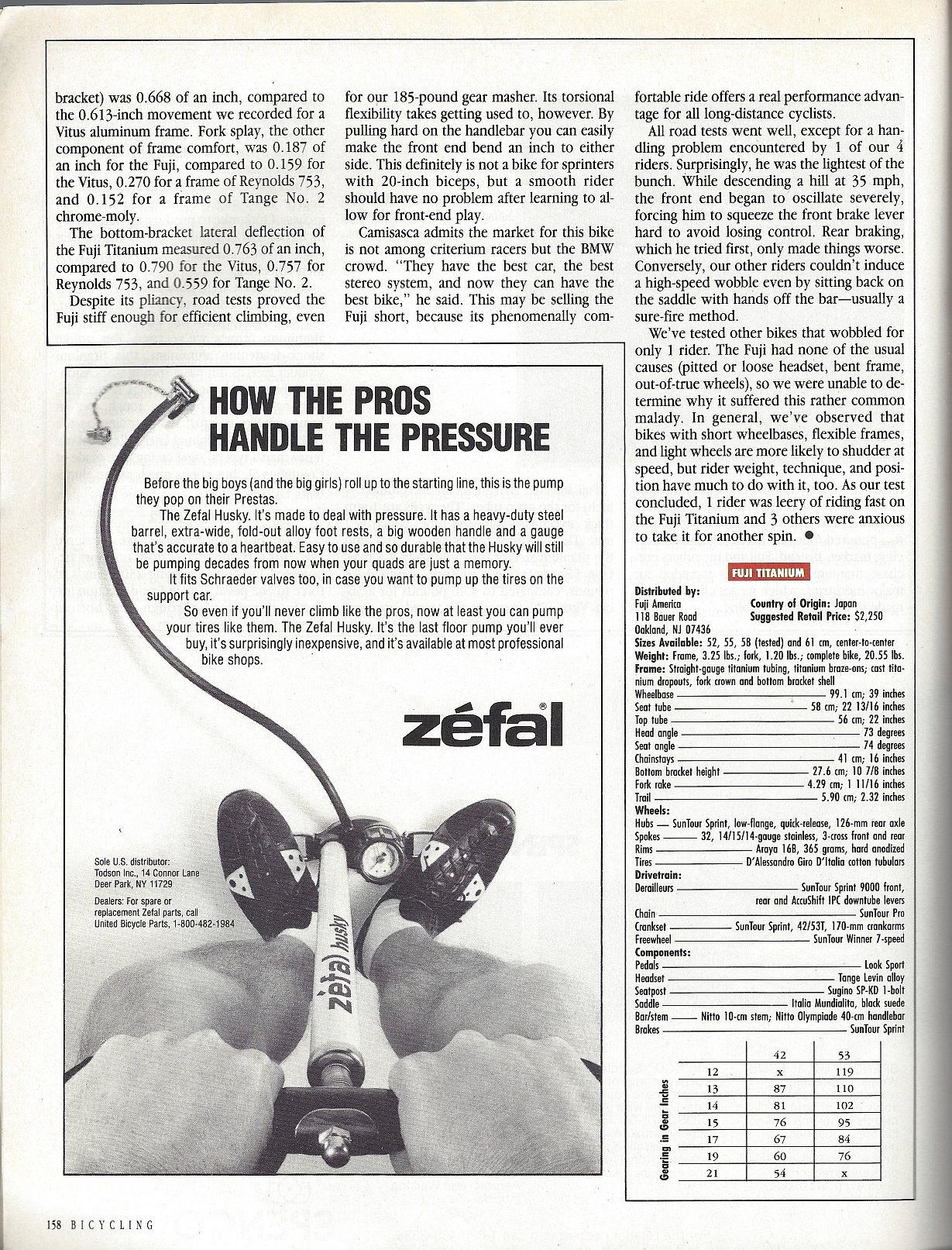

Famed manufacturer Fuji was one of the first Japanese groups to jump into the TITANIUM game. In fact, they may have been the first by a longshot, if the May 1987 Bicycling Magazine review is to be believed: according to this report, Fuji actually made a TITANIUM prototype all the way back in 1974! In any case, Fuji revisited the magic metal in the '80s, and under the guidance of master bicycle designer and former Olympic racer Shoichiro Sugihara, generated a marketable design. It would appear that the bicycle was sold in two slightly different iterations. The first was painted a "titanium blue" (whatever that means) and came with a chromoly fork. This configuration is described, although not pictured, in the 1987 article. By 1988, however, previously reported surface finishing problems had been worked out and, thereafter, the "Titanium" model was sold polished and unpainted, with a newly designed TITANIUM fork. It was the latter iteration that Bicycle Guide reviewed in their May 1988 TITANIUM bonanza issue. Both of the '87 and '88 reviews were positive, if not effusive. Remarkably, Fuji seems to have effectively engineered out excessive frame flex while only using 28.6mm (1 1/8") straight-gauge CP tubes, and even the 1984 Match Sprint World Champion Connie Paraskevin Young had good things to say about her Fuji "Titanium" (not that there's any evidence she ever rode it under more than casual circumstances). Road comfort was also praised.

Other than the good initial performance reviews, Fuji's offering was also noted for its remarkable adherance to traditional bicycle aesthetics, specifically with regard to the (horizontal, set-screw) dropouts and "braze-ons."

By 1989, however, Fuji's technical accomplishments would go on to be overshadowed by other manufacturers who had started using slightly oversized tubes. This suggests that the initial praise may have been more relative than absolute. I'd be curious to hear what Jan Heine has to say about it...

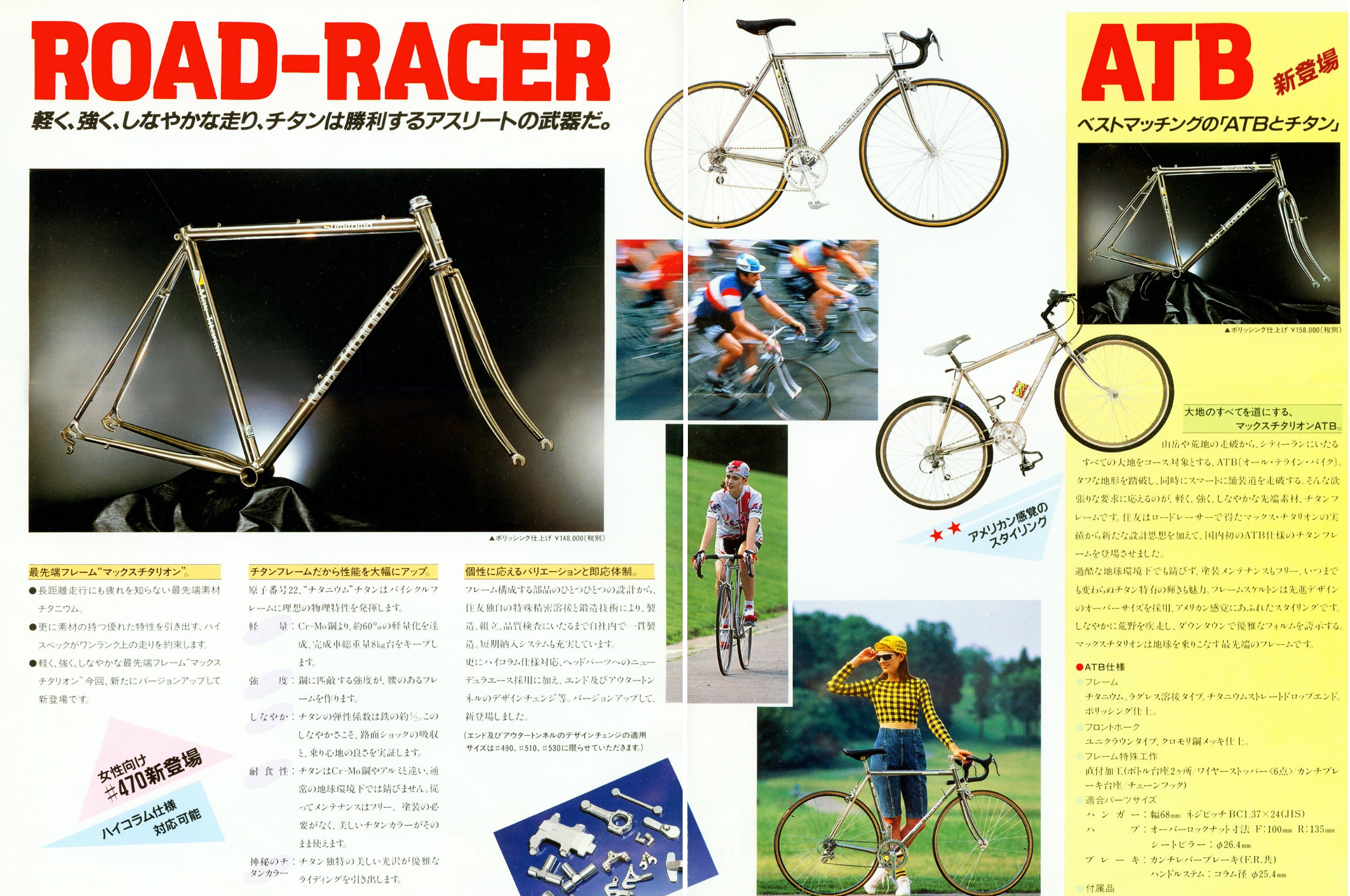

At some point prior to 1989, Fuji outsourced production of their TITANIUM frames to Sumitomo, a major OEM corporation. Sumitomo sold the same frame under their own name as the "Max Titarion" in 1990.

>>> 1987 Fuji "Titanium"

(Scans sourced from Bikeforums)

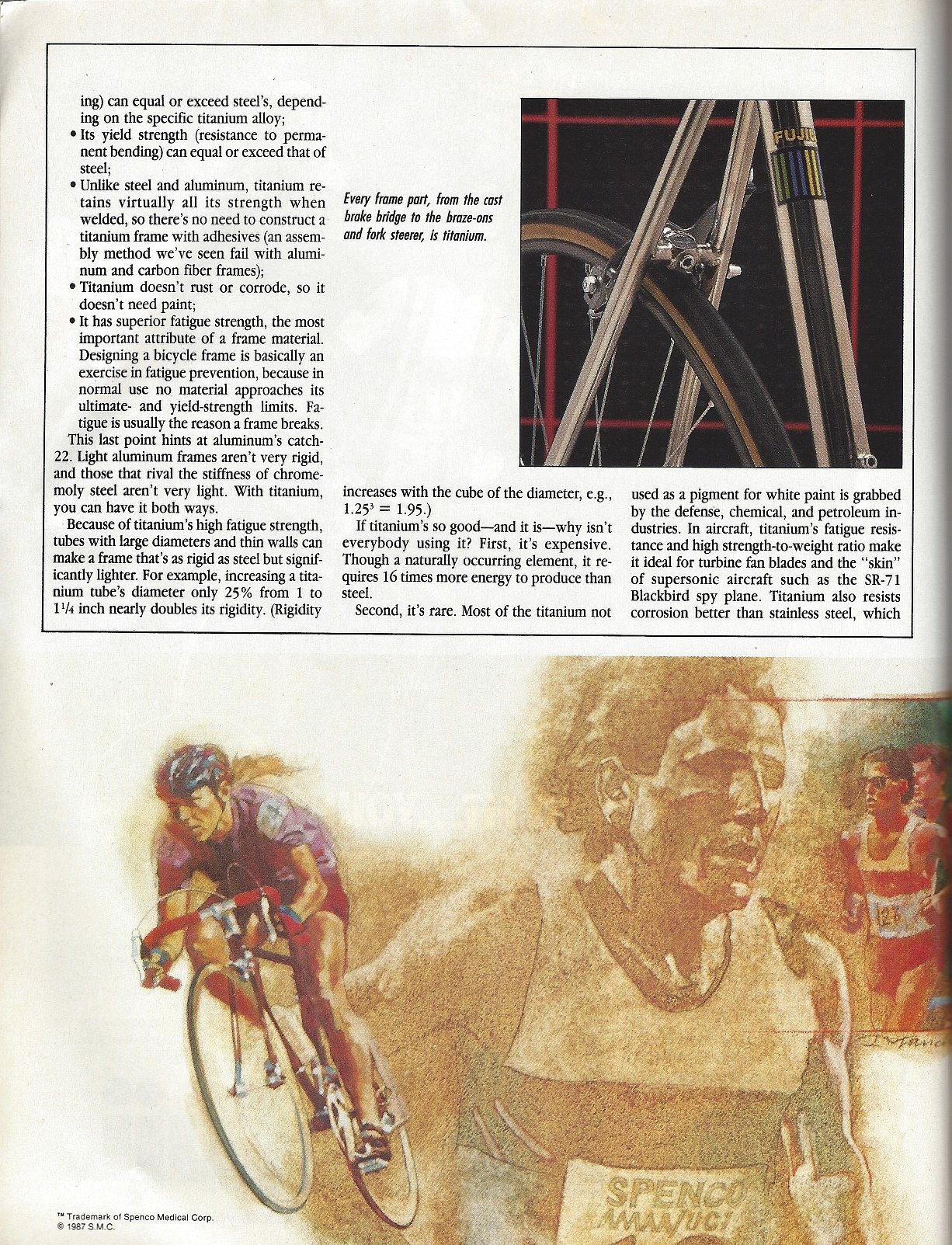

Aside from showing one of the earliest polished show bike examples of the Fuji "Titanium," this 1987 review also covers some metalurgic and engineering aspects of TITANIUM and contains some very interesting test results from multiple controlled flex tests comparing the TITANIUM frame to several aluminum and steel frames.

(Image sourced from RaodBikeReview)

Here we have one of the first few hundred Fuji "Titanium" frames imported into the U.S., bearing the "titanium blue" paint and chromoly fork mentioned in the Bicycling article posted above.

>>> 1988 Fuji "Titanium"

New for 1988! Polished and unpainted, with a newly designed TITANIUM fork and some very 80s decals. Also now manufactured by Sumitomo. But still very normal looking! It's a normal bike, guys, just made out of TITANIUM!

>>> Sumitomo "Max Titarion"

A mountain by any other name.

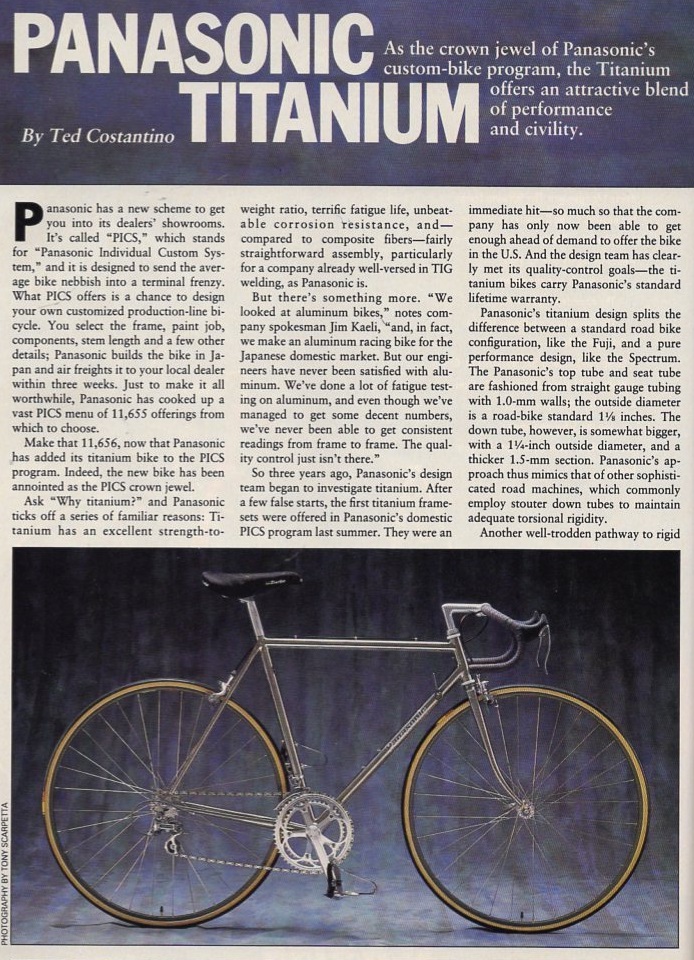

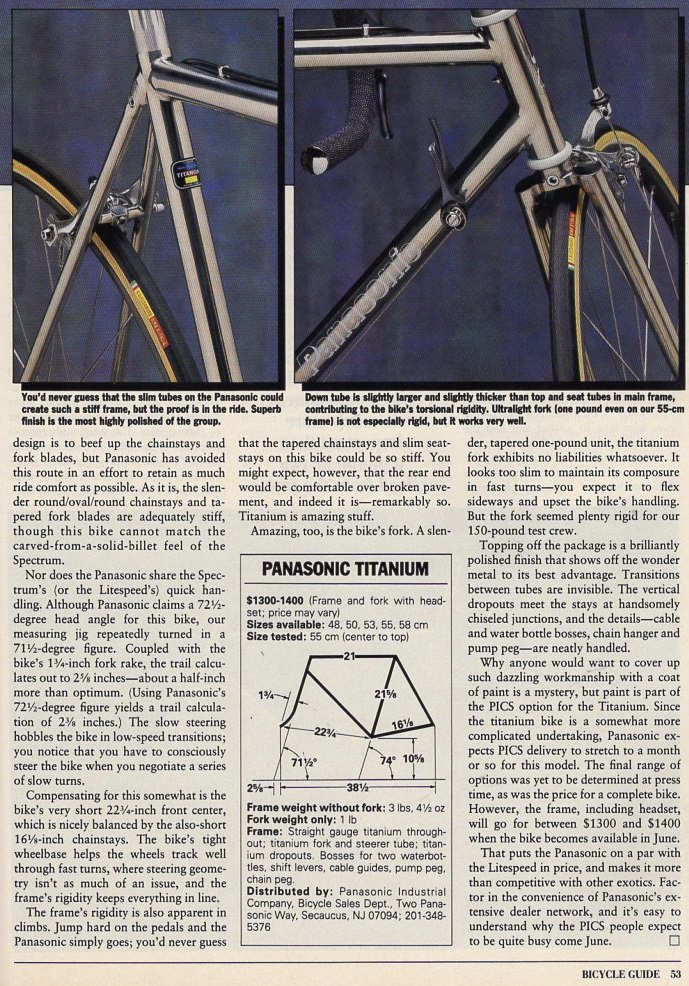

Panasonic, mostly known for VCRs and camcorders, apparently also manufactured their own TITANIUM bicycles, rather than outsourcing the welding to a major industrial outfit like Sumitomo. Panasonic's TITANIUM bicycles were available through the Panasonic Individual Custom System (PICS) program, and as such you can find pictures of these frames with various custom paint jobs.

>>> 1988 Panasonic "Titanium"

The review posted above gives the Panasonic bicycle moderate praise, criticizing aspects of the bike's geometry but complimenting the rigidity of the dainty looking TITANIUM fork and the neat welds. More pictures of the 1988 Panasonic "Titanium" can be found at Classic Cycle US and Panasonic Bike Museum.

>>> 1988 Panasonic "Titanium" track

(Image sourced from Pista Mercado on Facebook)

A rare custom track model "Titanium" PICS.

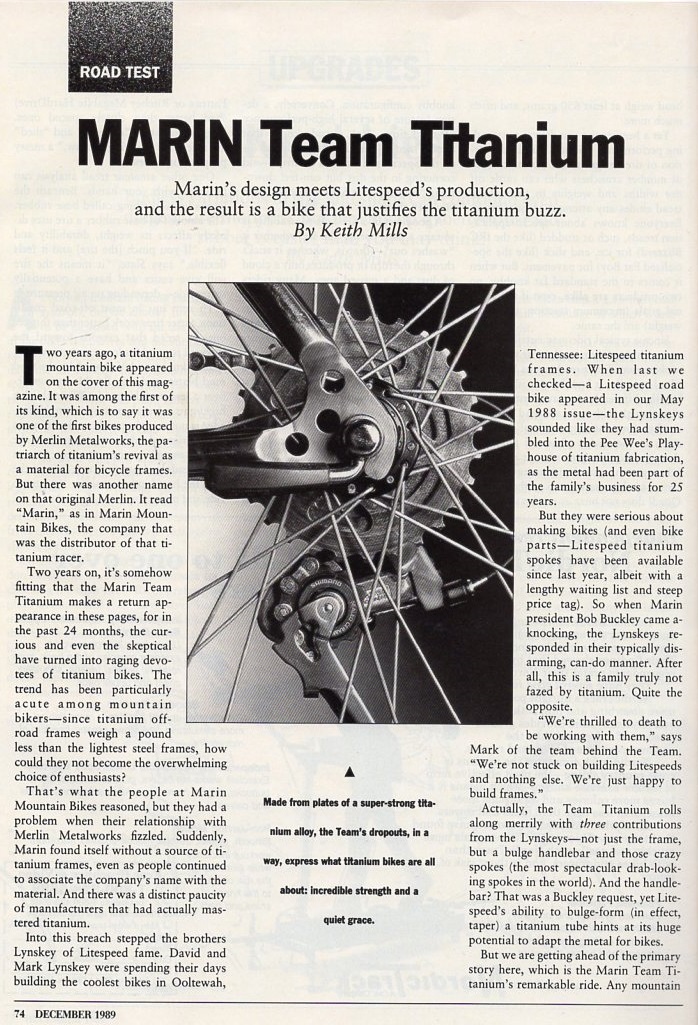

Marin bicycles founder Robert Buckley is reported to have gotten into cycling in order to rehabilitate his knee after a water-skiing accident. As the story goes, he bought his first bicycle from mountain bike legend Joe Murray, who was at the time working at a bike shop next to his house. Being a businessman engaged in lizard skin import/exports from Asia (really???), he used his connections in order to establish a new bicycle brand in 1986. Murray apparently urged Buckley to include a TITANIUM bicycle in his first catalogue, and connected him with Merlin, with whom Murray was in close contact. Some sort of disagreement caused Buckley to cancel his original Merlin production order, however, and thereafter he contracted with Litespeed for production.

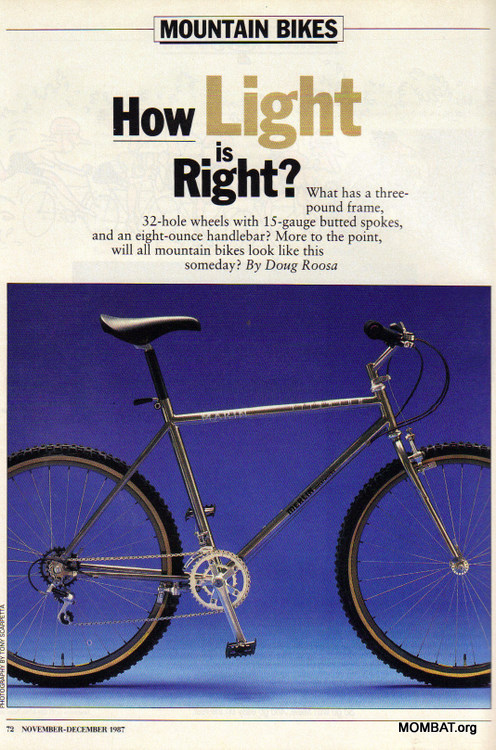

>>> 1987 Marin "Titanium" (Merlin)

(Scans sourced from MOMBAT)

The above article barely mentions Marin, calling it a mere distributor. In 1987, a lightweight TITANIUM mountain bike was still more of a tantalizing "what if" than an established fact. The article discusses various facets of lightweight off-road technology development.

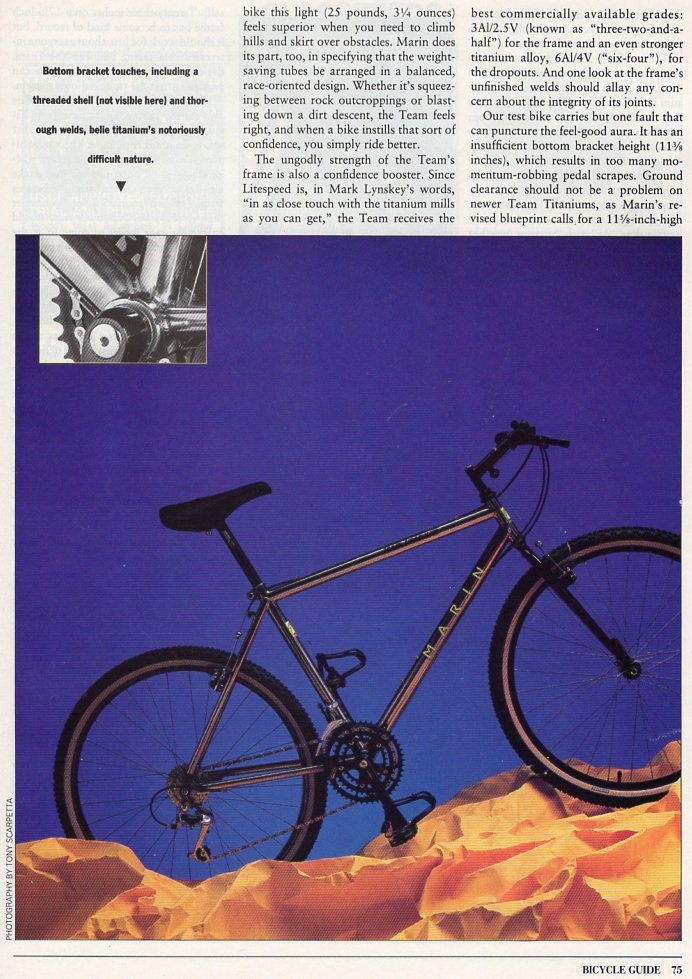

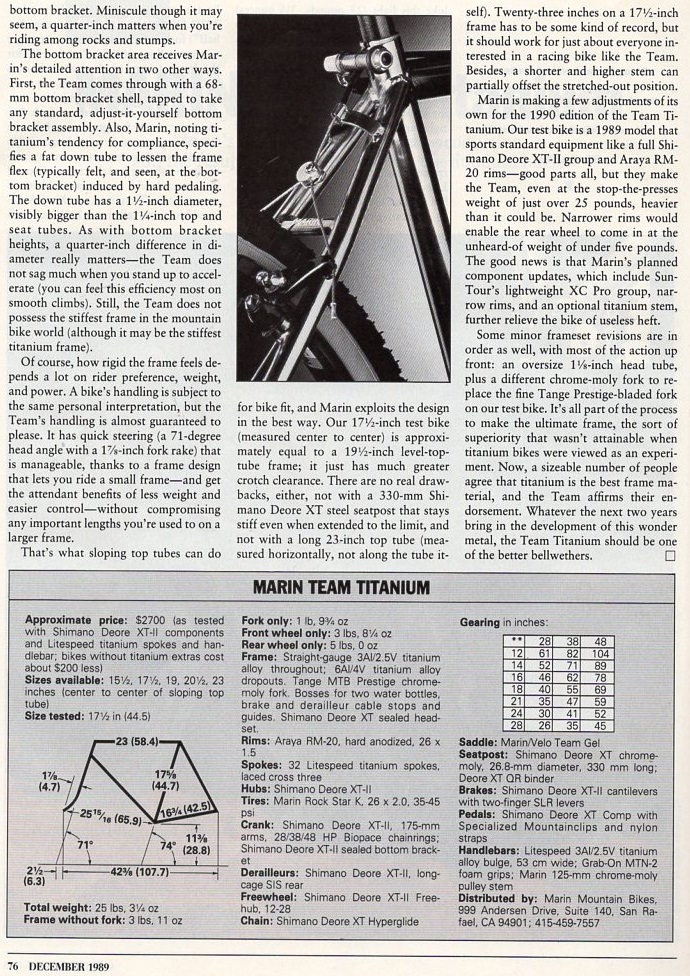

>>> 1989 Marin "Team Titanium" (Litespeed)

OldSchoolRacing.ch page on the Marin Team Titanium.

Two years after the first article, Bicycle Guide took Marin somewhat more seriously as a company, and had mostly good things to say about the revised "Team Titanium," which was at this stage being prototyped by Litespeed.

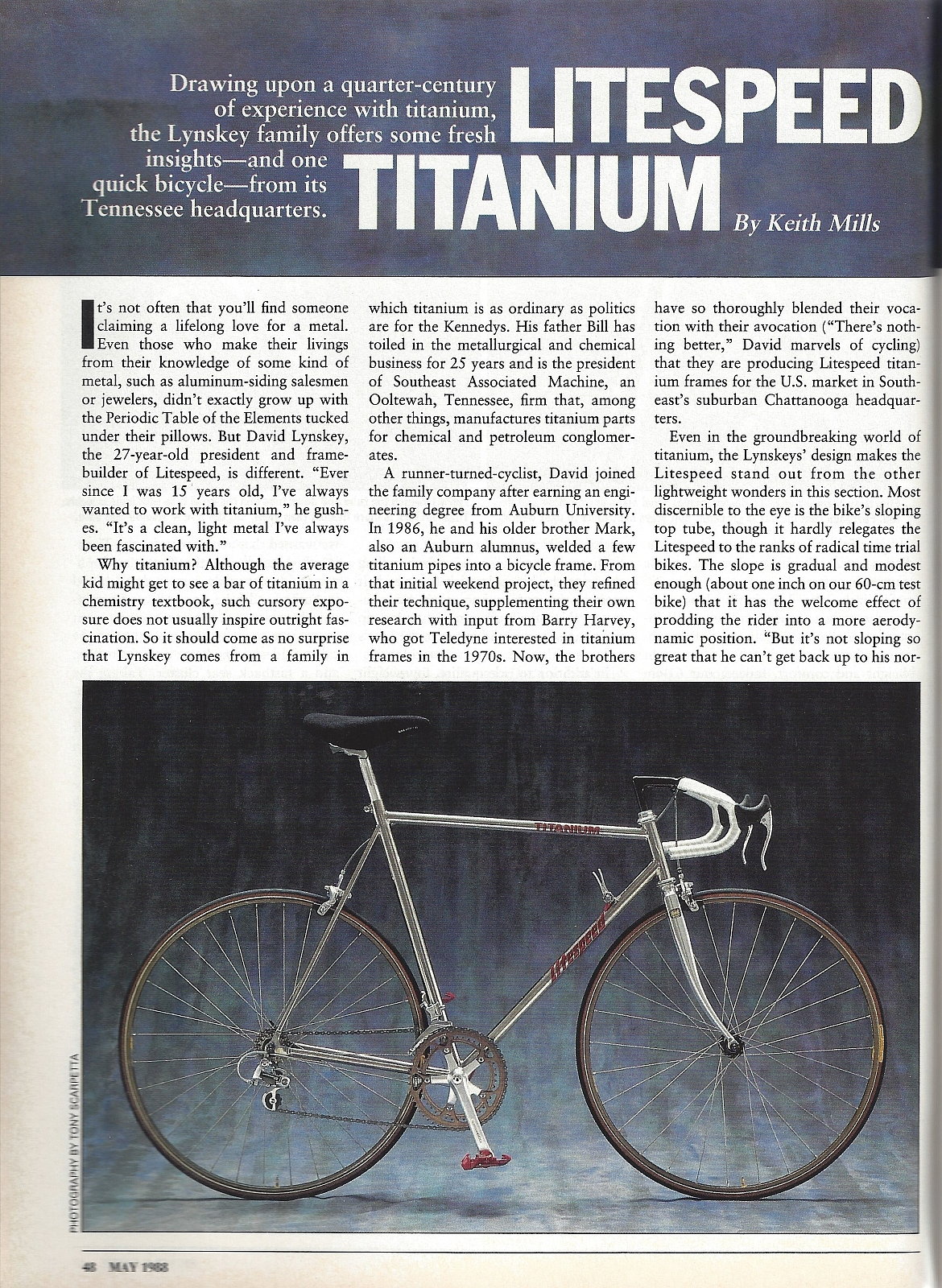

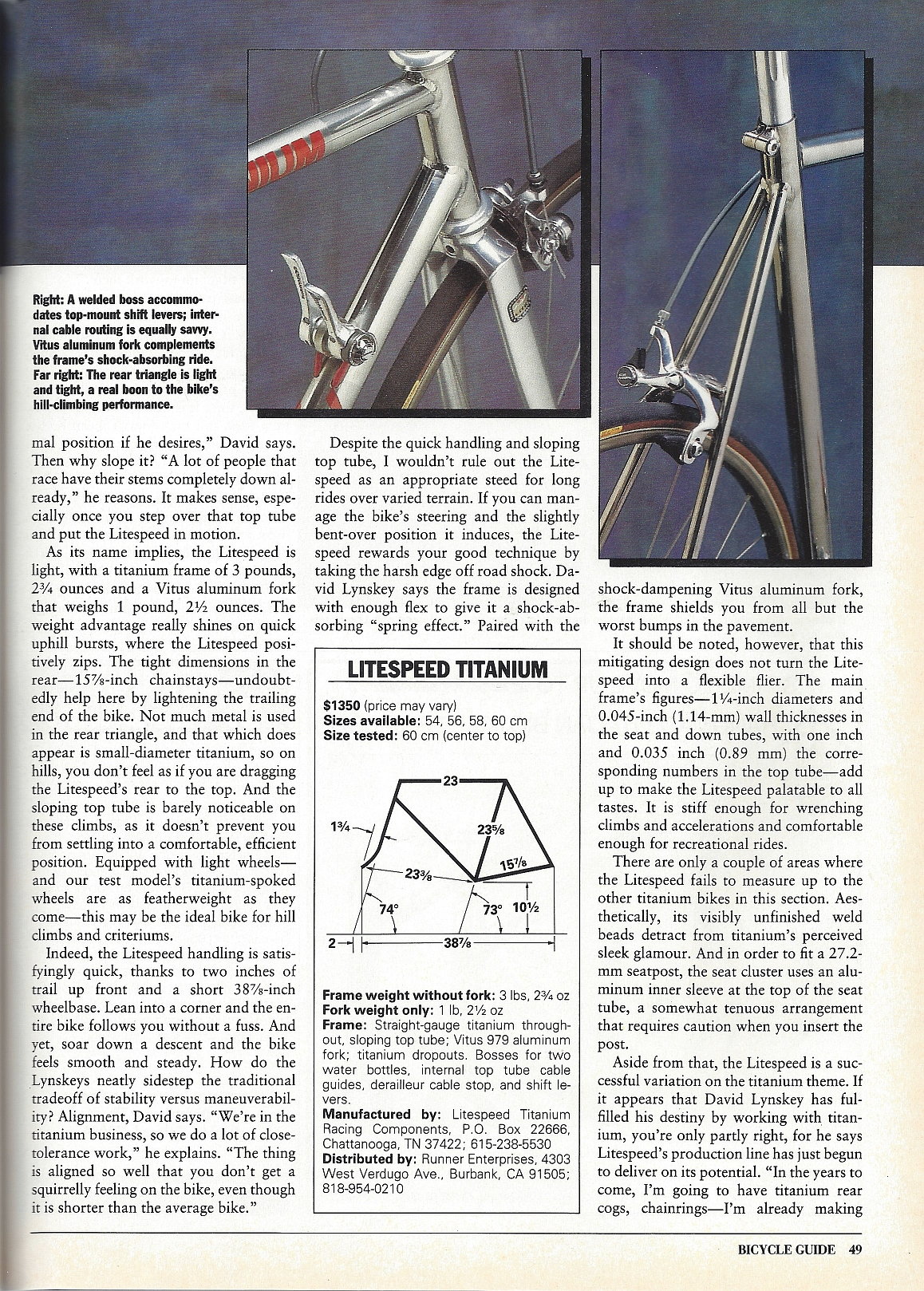

As a manufacturer, Litespeed approaches dynastic proportions within the world of TITANIUM. Litespeed's founders, the brothers Mark and David Lysnkey, are second-generation TITANIUM workers, and grew up around the metal. Mark and David started experimenting with TITANIUM prototypes in 1986 and, having receieved technical guidance from Barry Harvey (of Teledyne Titan fame), released their first production bike in 1988. Through the family's ties to Southeast Associated Machine, the Lynskey's were able to source 3al/2.5v tubing and 6al/4v stock for dropouts right from the start. Litespeed has gone on to become a pillar in the industry, and continues to focus primarily on TITANIUM bicycle production to this day.

>>> Undated Early Litespeed "Titanium" Distributor Sheet

(Scans sourced from author's personal archive)

The frame shown above is similar to the one tested by Bicycle Guide in 1988, except that the internal brake cable routing through the top tube enters on the drive side rather than the non-drive side, and of course the black-and-white frame doesn't show any shifter mounting accomodations at all.

>>> 1988 Litespeed "Titanium" Bicycle Guide Review

(Scans sourced from Bikeforums)

Litespeed's first model, in many respects a promising offering in the great TITANIUM wave of 1988, is now rather obscure. Only a few documents remain and most of the frames themselves seem to have perished. Unlike any of the other bikes released or advertised in 1988, this one made use of a forward-slanting top tube, somewhat reminiscent of the low-profile pursuit and time trial frames of the day. Even taking that into account, however, the Bicycle Guide reviewers did not rule out using the "Titanium" for"long rides over varied terrain." Ultimately, the frame was praised for its handling (a result of very precise alignment), and the the reviewers only took issue with the rough appearance of the welds and the fact that the seat tube used an aluminum insert. It's interesting to note that the test bike was built using early Litespeed-manufactured TITANIUM spokes, which would later appear in the 1990 catalogue.

I happen to own one of these frames, and detailed pictures can be seen HERE. My production model differs in a few respects from the early examples shown above, most prominently in the dropouts.

Miyata Gun Works built its first prototype bicycle, using gun barrels for the main tubes, in 1890. Let that sink in.

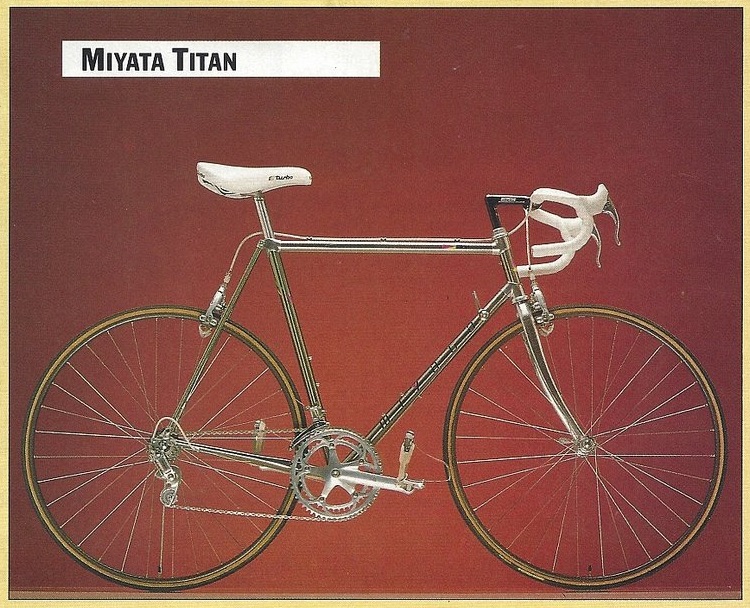

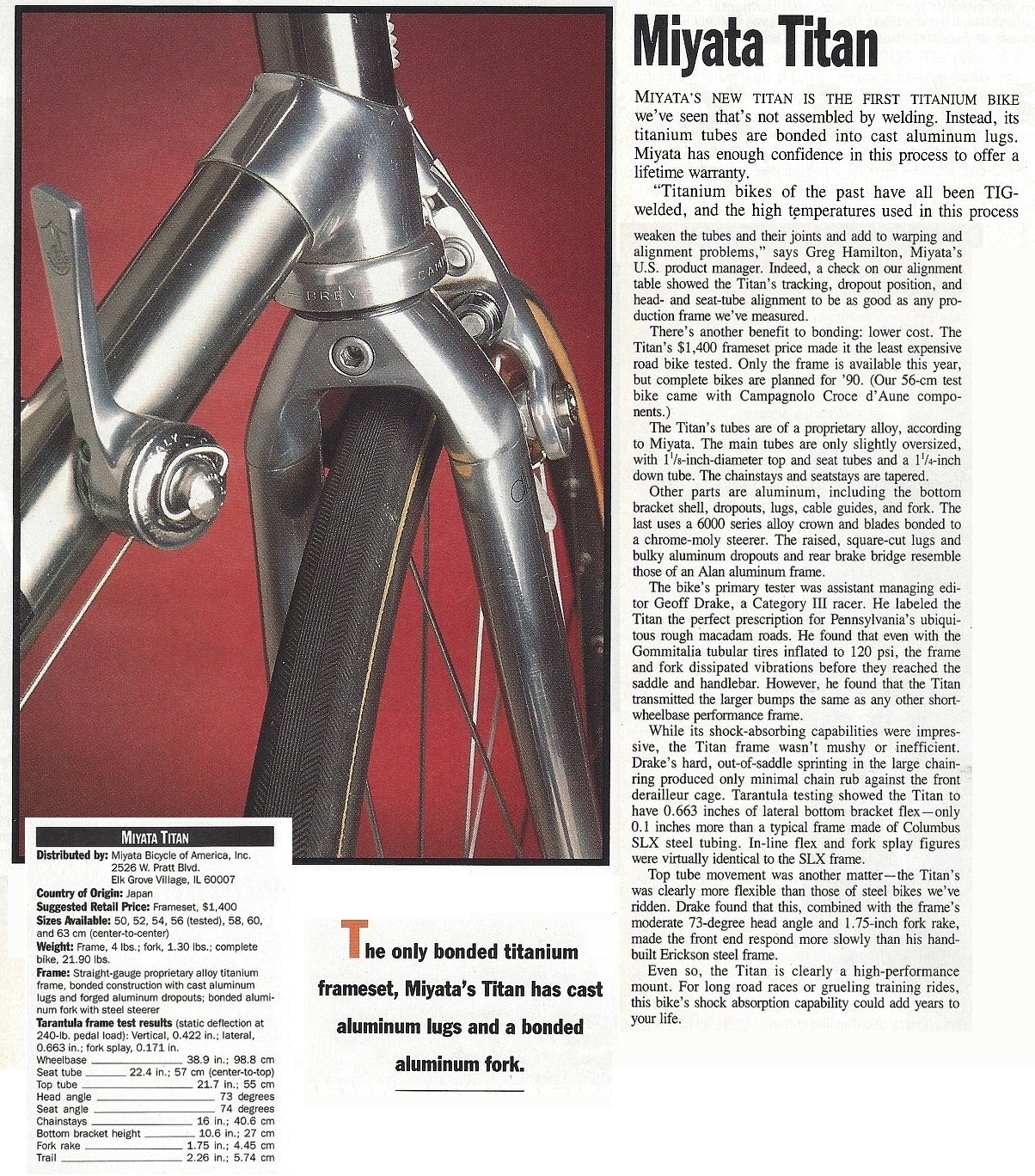

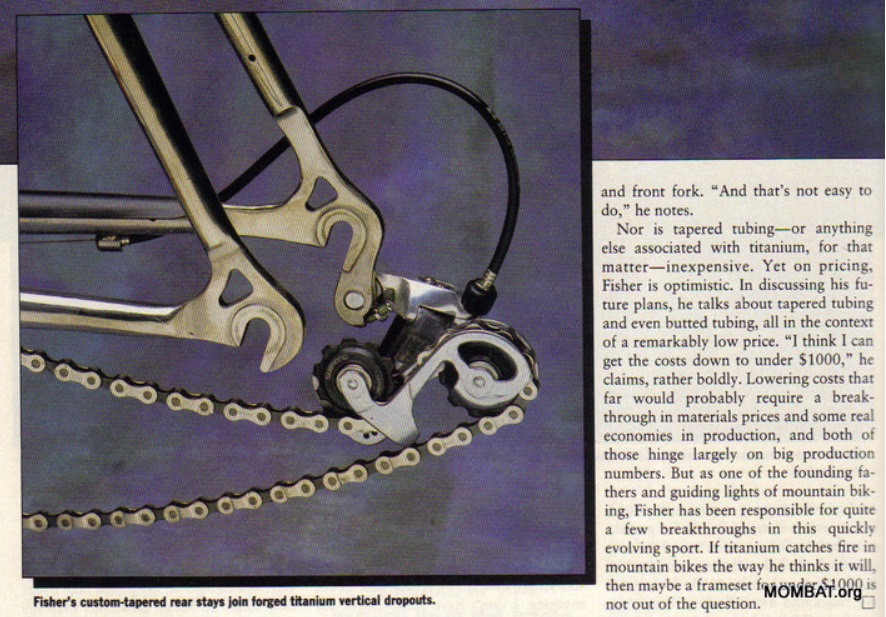

Over the decades, Miyata gained a reputation for design and manufacturing innovation through its construction of war implements, bicycles and motorcycles, and is rumored to have pioneered the use of tripple-butted tubes. By the 1980s, Miyata was ready to jump into the TITANIUM game, but not in the same way as most other manufacturers. Rather than welding TITANIUM tubes together, they decided to bond them using chemical adhesives.

The use of dissimilar materials for lugs and main tubes, joined by mechanical and/or chemical means in order to produce a frame, has a long history in the world of bicycles, probably starting with bamboo bicycles at the turn of the century. The French would keep the tradition of non-soldered construction alive with Duralumin bicycles like the Caminargent of the 1930s and the AVIAC of the 1950s, with main tubes that were bolted, pressed and/or glued into the lugs. All of these frames exhibited certain structural deficiencies, however, and tended not to last under hard or sustained riding. The aerospace boom of the 1970s, however, led to advancements in chemical adhesives that would make bonded bicycle frames a serious option for professional racers and casual riders alike. Alan is the best remembered and most succsful out of this generation of manufacturers, but Carlton, a subsidiary of Specialist Bicycle Development Unit of Raleigh bicycles, Graphite USA, and Graftek Exxon also pushed bonded frame construction forward. By the 1980s, most of the kinks had been worked out, and epoxy bonding had become a relatively safe and reliable construction method. This being the case, Miyata decided that a bonded TITANIUM frame might have a place in the new market as a more affordable option (as cutting out the difficult and time-consuming welding process would streamline construction to a considerable degree).

>>> 1989 Miyata "Titan"

(Scans sourced from BikeForums)

The review for the bonded Miyata Titan above is mostly positive, but not "pull-your-hair-out-and-gnash-your-teeth" good. Bottom Bracket flex was minimal, but top tube flex was noticable. Miyata tried to make the bonded frame construction sound like an engineering feature, rather than just a cost-saving measure, since their TITANIUM tubes were not subjected to welding heat and therefore were less likely to warp or crack. I owned a Miyata T6000 briefly. It looked like it had been ridden hard and still had plenty of life left in it. It was not very light though.

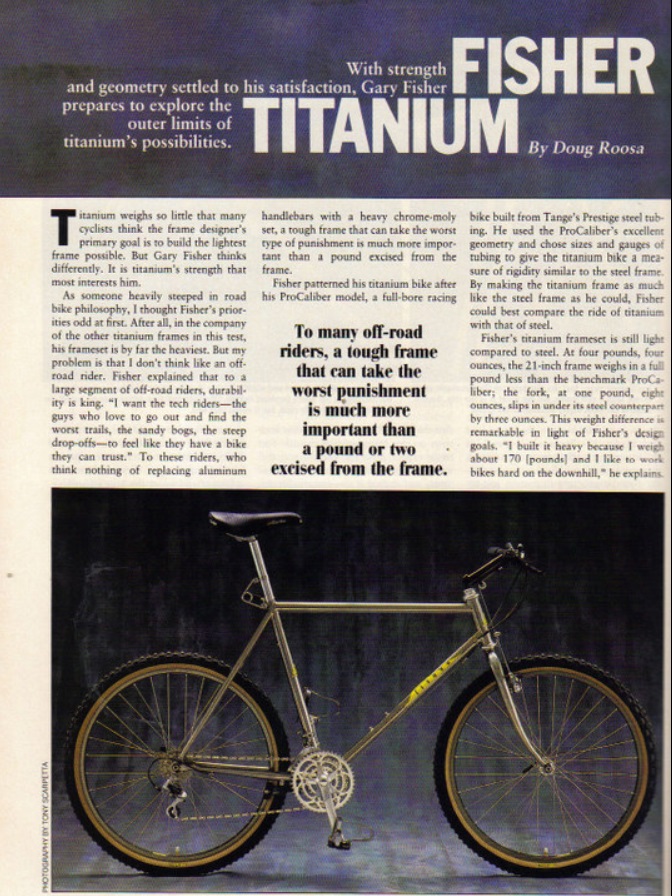

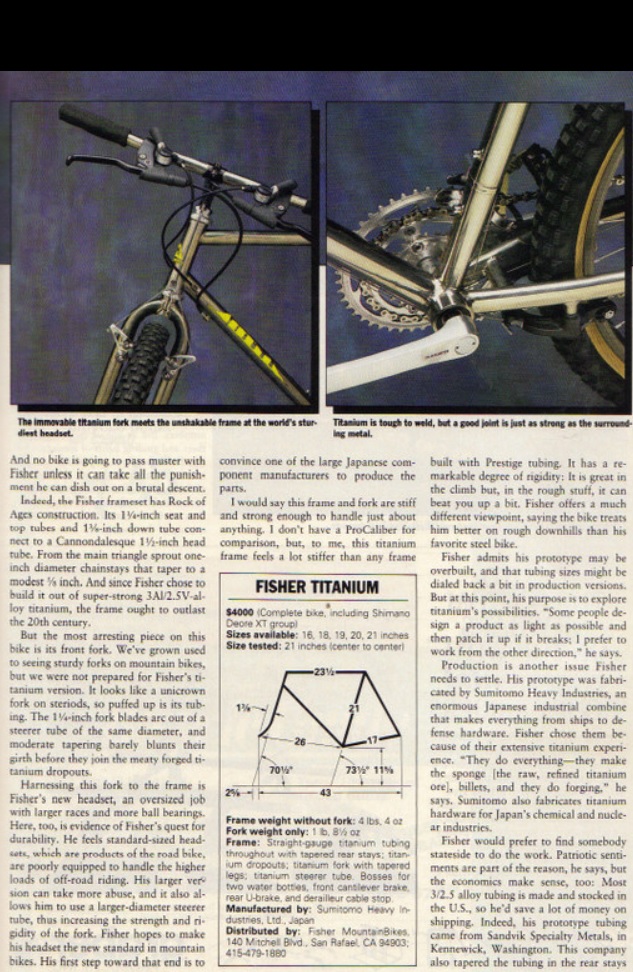

Gary Fisher was a central figure in the very first wave of West Coast mountain biking. In fact, he helped to coin the term "Mountain Bike". He, like several others from the California scene, would go on to own a large and prosperous bicycle manufacturing company. Unlike some others, Fisher would continually push the proverbial envelope, chasing after innovation high, low, and wherever it might suggest itself.

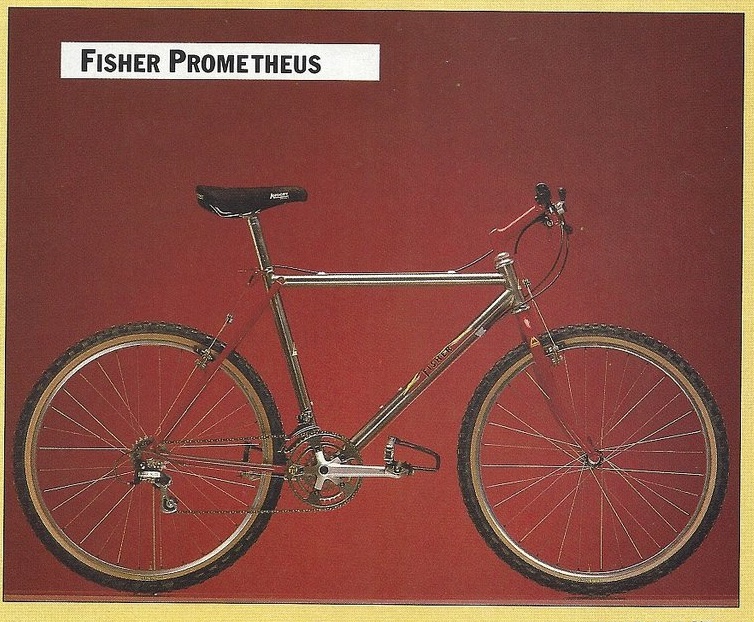

>>> 1988 Fisher "Prometheus"

(Scans sourced from MOMBAT)

Fisher's "Evolution" system, consisting of oversized main tubes, head tubes/headsets, seat tubes/seatposts, and even in some cases 80+mm wide bottom bracket shells, certainly stood out. In the sea of flexy TITANIUM bicycles, Fisher's prototype Prometheus (here made by Sumitomo Heavy Industries) stood an island of almost harsh rigidity, if you believe the reviewer.

Mike Augspurger, of Merlin, and later One-Off Titanium fame, told me about the genesis of Gary Fisher's 1 1/4" "Evolution" headset design: recalling first one of his own early prototype TITANIUM forks with a 1" steer tube, he says "it's a pretty good fork, even by modern standards. It's the weight of a carbon fork. Well the problem was the 1-inch steer tube. That diameter just isn't stiff enough with titanium. That's why Gary Fisher came up with the 1 1/4-inch headset size. He wanted to make a titanium fork, so he got his engineers to give him the calculations, and they said if you want to match the stiffness of a 1-inch steel steerer, you have to go all the way to 1 1/4-inch with titanium. So he said ok I'll make my own headset size. Which was just crazy, but, he did it."

>>> 1989 Fisher "Prometheus"

(Scans sourced from BikeForums)

Perhaps ironically, this interesting prototype (built by Sandvik in Kennewick, WA) uses a steel fork rather than titanium, while maintaining the 1 1/4" steer tube diameter originally designed to mitigate the flexibility of TITANIUM. Bill Stevenson, the production manager at the time, would go on to have his own titanium frames produced in the 1990s. Come to think of it, Stevenson has had a hand in all sorts of interesting projects! More pictures of an example from this run of prototypes can be found here.

Images of the later 1990 production model Prometheus, which discards the chromoly stays in favor of full-titanium construction, can be found here and here.

Founded in 1974 by Skip Hess, Mongoose's first product was the cast-magnesium MotoMag BMX wheel. Bicycle frames came a bit later, first BMX and then, in 1985, All Terrain Bicycles (reviewed here). Now mostly associated with low-price department store bikes, Mongoose has a history of producing high-end racing machines. In fact, Mongoose was a bona fide trendsetter. The 1988 Mongoose Tomac Signature, a Tange Prestige steel bicycle, stood apart from other manufacturers' "signature" models in that it was a near-exact replica of the actual race frame used by Tomac in the previous season, and featured such advanced features as rear cantilever brakes and ultra-steep 72 degree head tube angle (you can read a review of that model at MOMBAT).

For 1989, Mongoose decided to up the ante with a TITANIUM version of Tomac's bike. Per the 1988 Bicycle Guide review that you can read at MOMBAT, linked above, the original plan was to have a Japanese manufacturer (probably Sumitomo) produce the frame. Ultimately, however, Mongoose decided to contract with Merlin, a decision that dedicated collectors have been happy about ever since.

>>> 1989 Mongoose IBOC series John Tomac Signature

(Image sourced from Second Spin Cycles).

One of the most revered and sought-after of the early TITANIUM mountain bikes. Note the mono-stay rear triangle, a possible first in TITANIUM (although Lavoie, below, also built mono-stay bikes in 1989). What makes it so cool, you might ask? I think, perhaps, that it stands as a distillation of the exciting period when mountain bikes were enjoing a meteoric rise but had not yet lost all of their simple, clunky charm.

You can see more pictures on this Retrobike thread and at Merlintitanium.com.

That's the only logo for Lavoie that I have access to, but it's definitely from the sophisticated 1990s. Look at how gothic and industrial it is! I suspect that they had a simpler, cleaner logo in the 80s, but of course there's not very good evidence of that. There's the tiny, blurry logo printed on the shirt that the guy on the right is wearing. Anyway, it bugs me having the 90s logo for the company profile in the 80s section. Aargh!

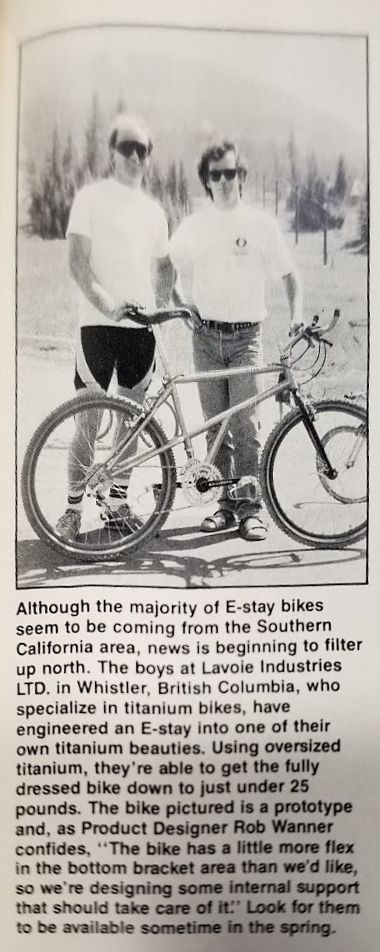

Lavoie Industries, Ltd. was, at the time of the article printed below (1989) located in Whistler, BC. If I had to describe Lavoie bicycles in one word, it would be "rare." They are rare bikes. Most of what I know about them comes from this Retrobike thread. There's also this text on the Gt Xizang, a Facebook post which suggests that Lavoie might have had a hand in prototyping Rocky Mountain's TITANIUM bicycles in 1989, and also a brief mention of Lavoie in a write-up about Dave Levy of Ti Cycles.

>>> 1989 Lavoie "E-Stay"

Looks like a cool bike to me.

And now, a special interview regarding the TITANIUM bicycles of the Soviet Union!

Artem is a bicycle enthusiast and owner of the only ЦКТБ (Central Design Technical Bureau) TITANIUM track bicycle in a private collection. I interviewed him via INSTAnt-TeleGRAM™.

From wikipedia: "The Central Design Technical Bureau of Bicycle Building was established in 1954 at the Kharkov Bicycle Plant. It was a separate organization and was not a structure of the design bureau of the bicycle factory. The purpose of creating such a powerful specialized institution was to develop new models of bicycles, in particular, sports, champion cycling equipment."

Ann: Titanium production and construction in the Soviet Union would have been a military project to begin with. Were the first titanium bicycles ordered by the government for racing purposes or were they the product of individual designers who had access to titanium fabrication tools through their work?

Artem: The USSR had command economy, therefore all the bikes officially manufactured in the country were limited to certain models ordered by the state. Basically, there was only KHVZ to produce racing bikes for ordinary people. Namely Старт-шоссе, Спорт-шоссе, Харьков and Чемпион-шоссе for road and Рекорд, Квант, Метеор and Спорт for track. All steel.

As for the famous ЦКТБ takhions, ordinary folks couldn’t buy those. They were only manufactured for professional teams.

There were some other factories and projects, but nothing remarkable.Therefore there are no soviet titanium bikes of serial production in existence.

The only official titanium prototype by ЦКТБ failed. In my opinion, it’s the reason.

Evidently, no one except for the state could import foreign frames. But a lot of people had access to non-secret military plants through their friends and so. There is still lots of soviet stuff from those factories around like titanium shovels, car skid plates, fishing rods, backpack racks, country house water tanks and other strange things.

People used to sneak stuff from any state job on hardcore level haha (Of course, frames weren’t an exception for this practice).

Military plants engineers usually had exceptional expertise in welding, so most of that stuff was cool in terms of craftsmanship, but they only had basic tubes so the lugs are often pretty ugly.

A "typical" frame illicitly built by a military plant engineer (Images sourced from Instagram user @moscowtape)

Ann: Do you happen to know the nature of the failures that the цktб frames suffered? Like fractures at the weld stress zones or broken dropouts?

Artem: Well, it’s hard to tell as those prototypes were destroyed during their own tests. I believe, it’s impossible to find those reports. As I know, only a couple of them was destroyed and the project was cancelled shortly after.

But ЦКТБ used titanium in their wheels, seatpost bolts, axles and so... I know that those titanium spokes usually burst. Titanium isn’t nice in terms of making spoke heads. Other than that… haven’t heard of any problems with their titanium parts.

Ann: Do you know the year those frames were made?

Artem: Unfortunately, no. I believe, those prototypes could be initiated by the ЦКТБ itself and not the government. So no official reports or materials were published.

Ann: Presumably before about 1989 though?

Artem: Yeah, I assume that even earlier Pioneer titanium road bikes started off in 70s or so? I think that ЦКТБ could have borrowed the existing technologies way better by 1989. Not sure anyway.

>>> ЦКТБ Titanium Track

(Images sourced from Instagram user @moscowtape)

"The holy grail of the Soviet Track racing hah."